From The Archives: 'Sticks and Bricks'

A flurry of recent articles has documented the extinction of a once-ubiquitous feature on the streets of New York City: the pay phone.

In their heyday, pay phones offered a convenient, cheap, relatively anonymous form of communication (though certainly not a secure one). Criminals used them regularly. Spies, too, employed pay phones to engage in coded conversations with sources and other contacts.

Spies and other clandestine operators tend to have a bifurcated approach to technology. As one incisive former CIA official once told me, in the world of espionage, it's already the twenty-second century. I’ve heard about high-tech, bespoke systems used to communicate with sources in despotic regimes, stuff that exceeded my wildest imagination.

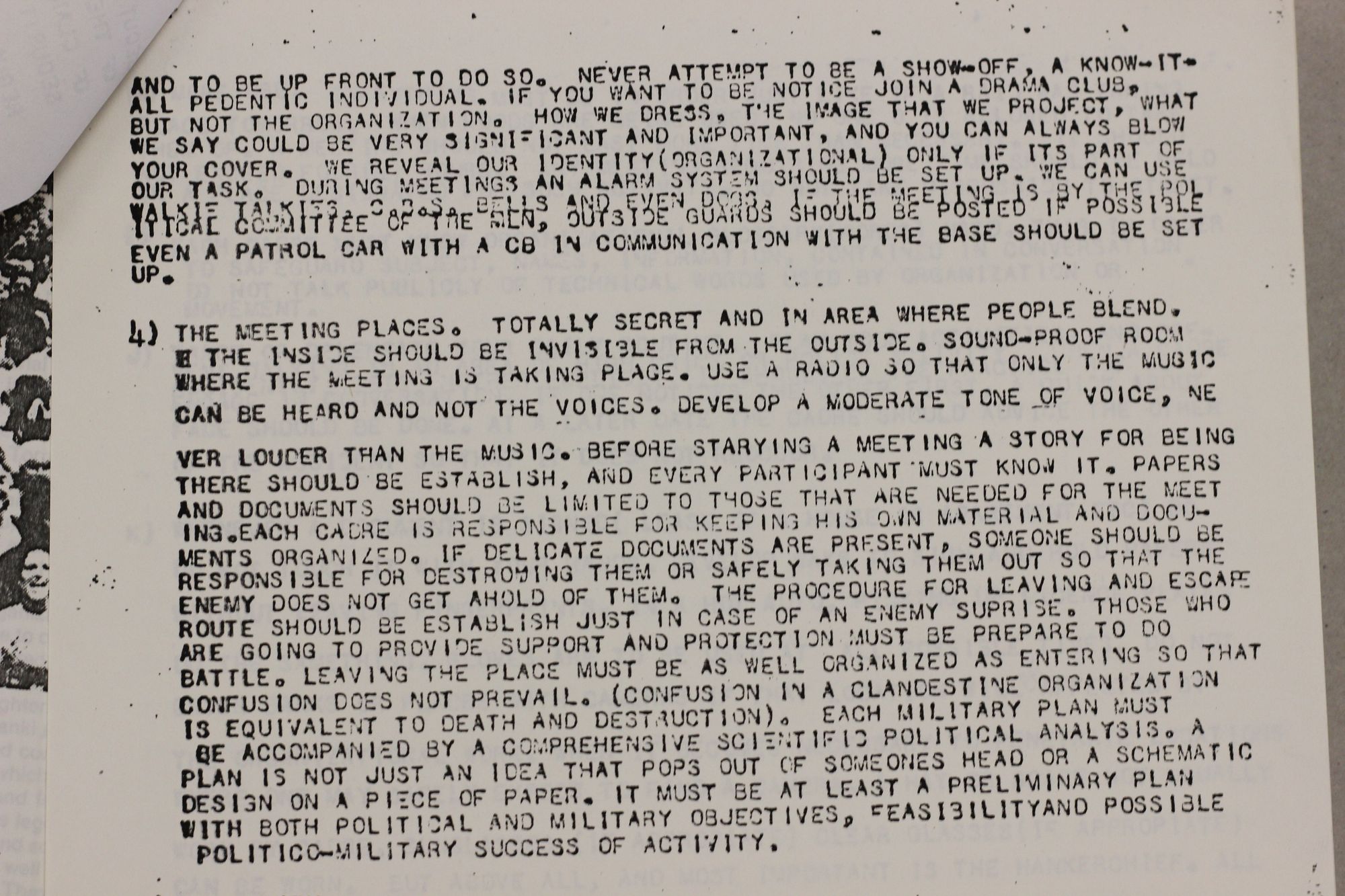

“Confusion in a clandestine organization is equivalent to death and destruction,” the guide says

Yet tradecraft in the field of human spying often still relies on certain core techniques. This is the world of chark marks and one-time pads, of (yes) brush passes and dead drops, of “sticks and bricks”—that is, hidden messages used by spies, stuffed into nondescript objects designed to blend into the surrounding environment to facilitate secret communication between intelligence operatives and their sources.

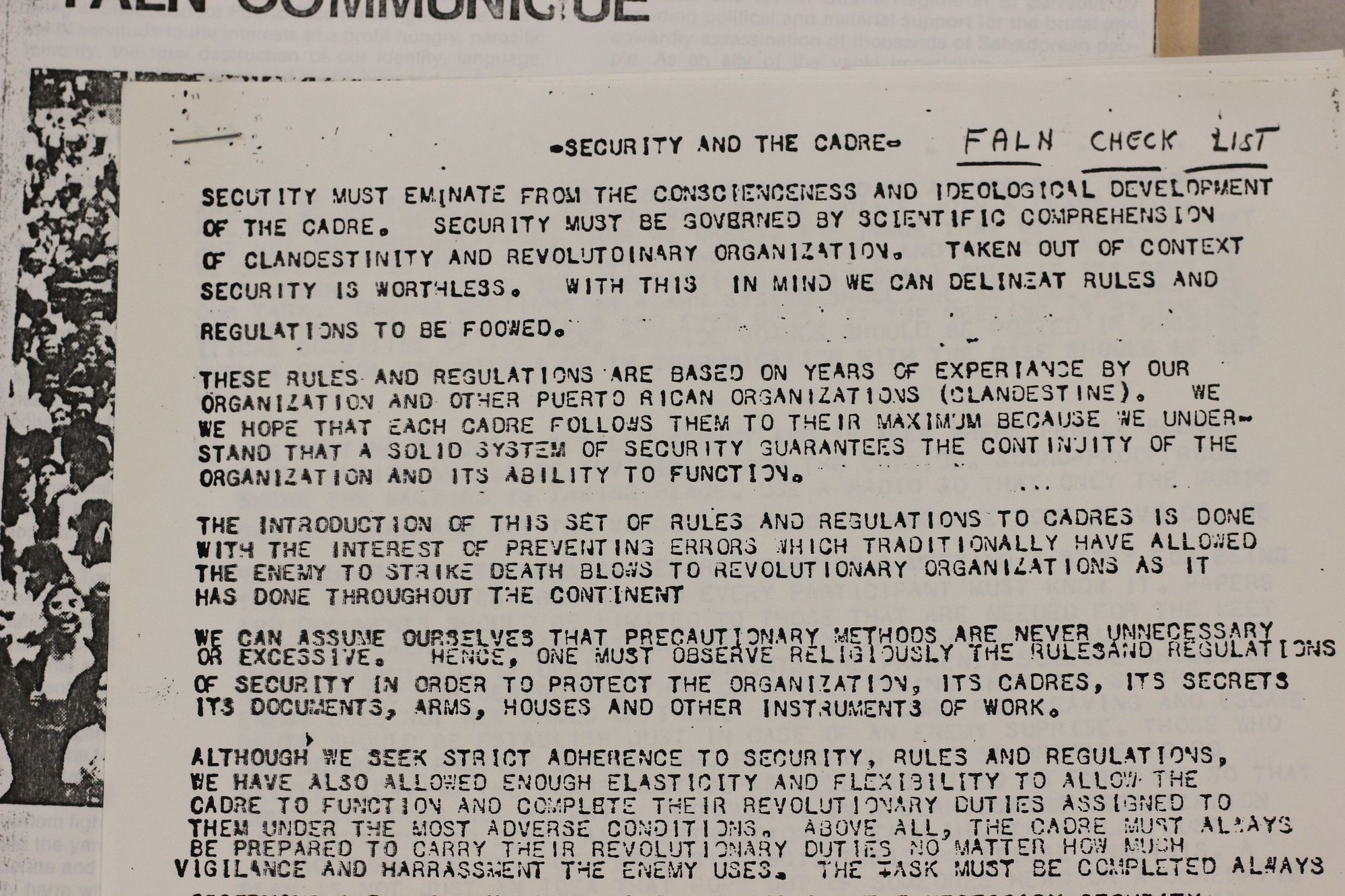

A few years ago, I came across a document in the Hoover Institution Archives, buried in the personal papers of a former Congressional staffer: a tradecraft training manual once used by the FALN, a pro-independence Puerto Rican Marxist terrorist group active in the 1970s and 1980s. The FALN was, by far, the best organized, most sophisticated terrorist organization operating in the United States in this period, and likely in the entire pre-9/11 era. In the 1970s and 1980s, it carried out over 130 bombings in the country. One 1975 bombing by the FALN in New York killed four and wounded 63.

Here's the full selection of images from my trip to the archives.

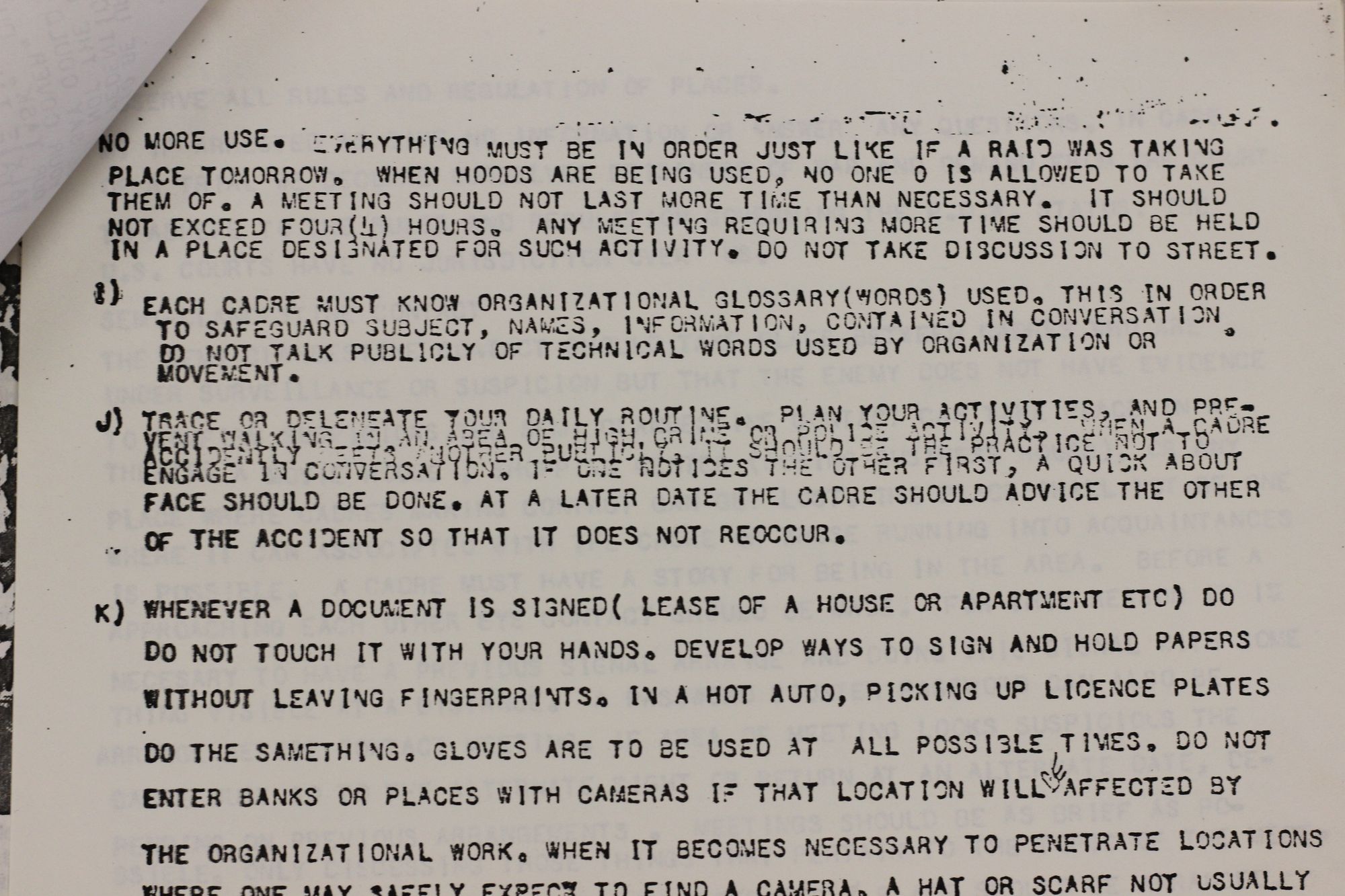

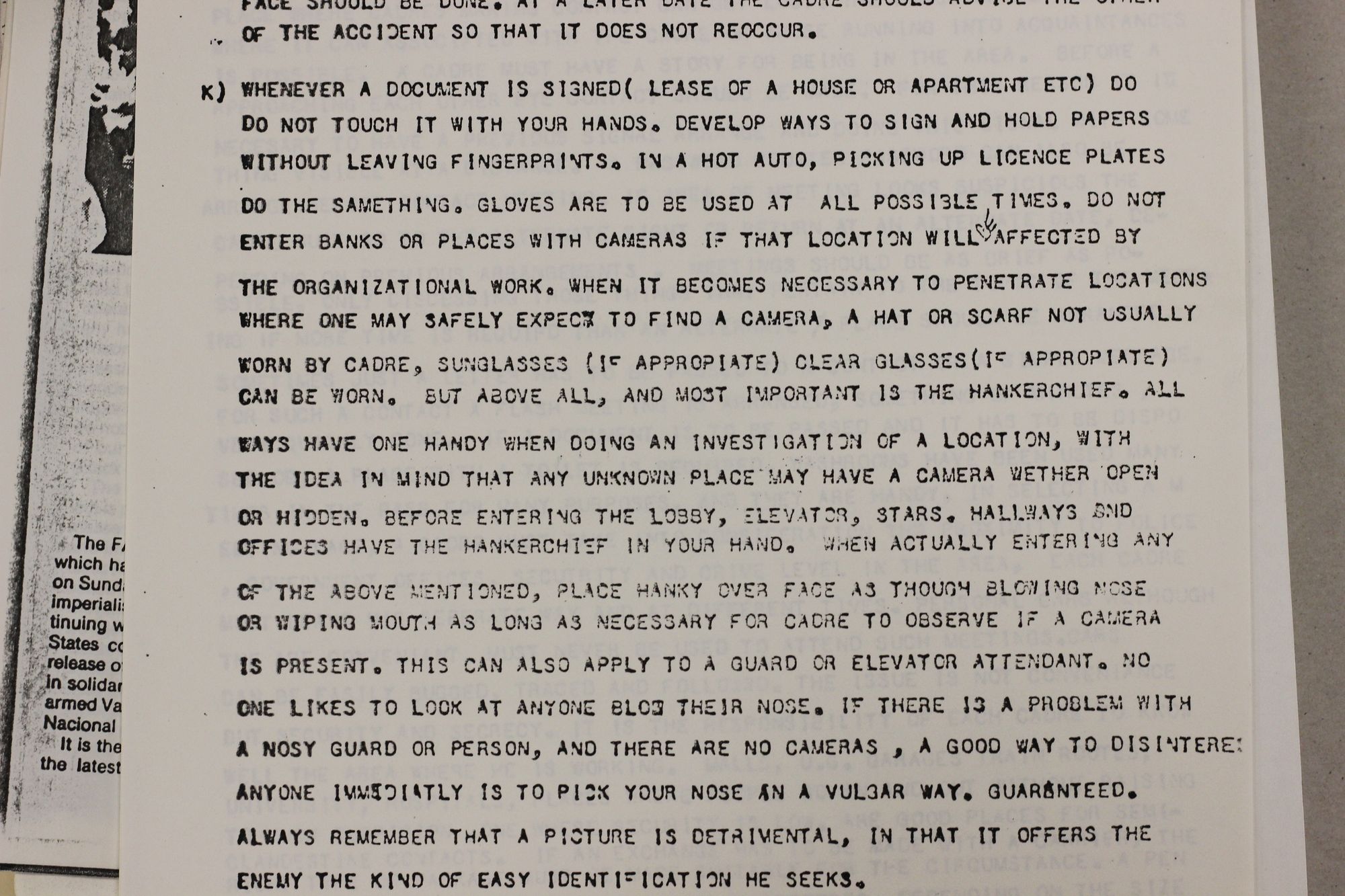

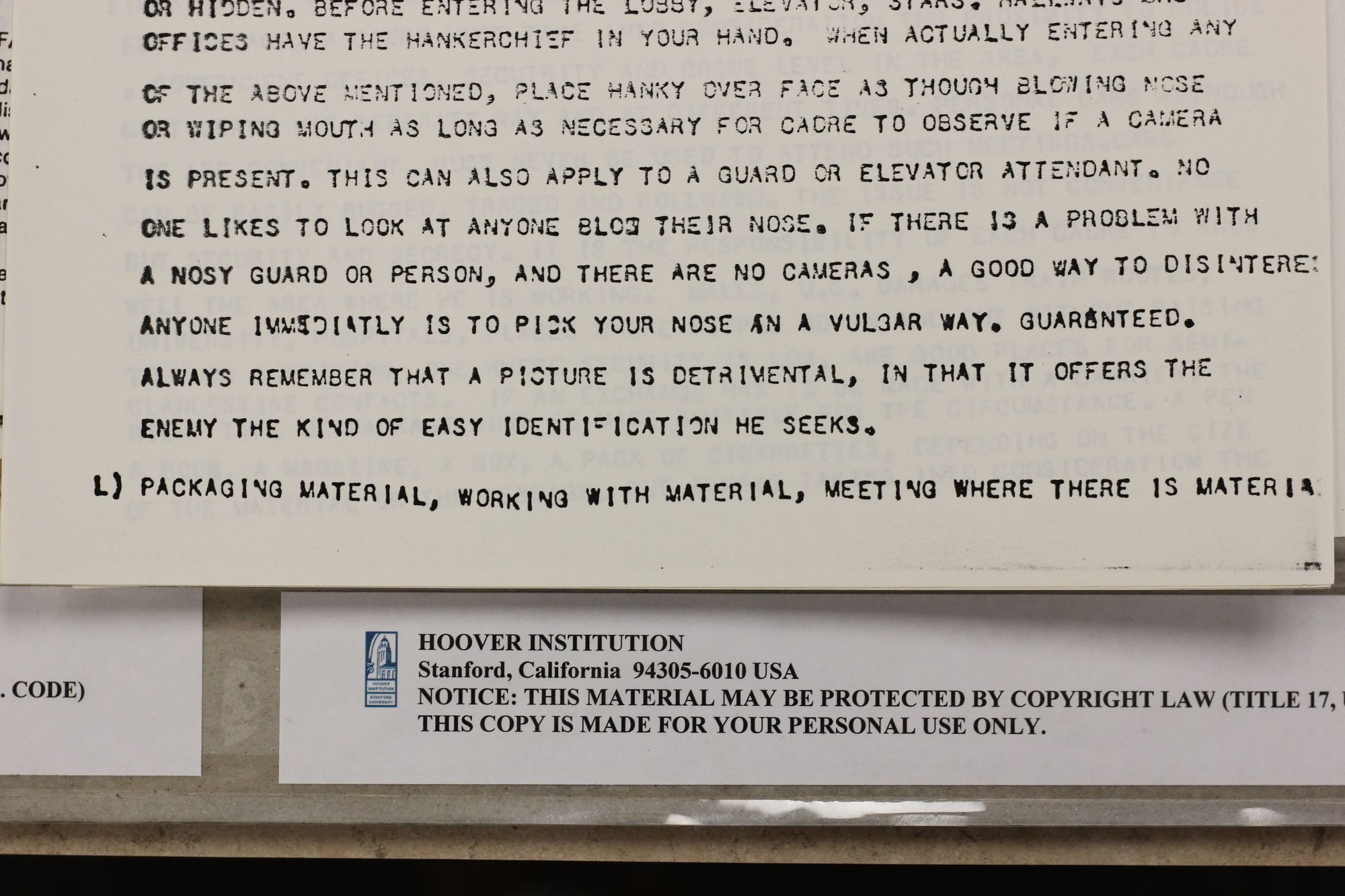

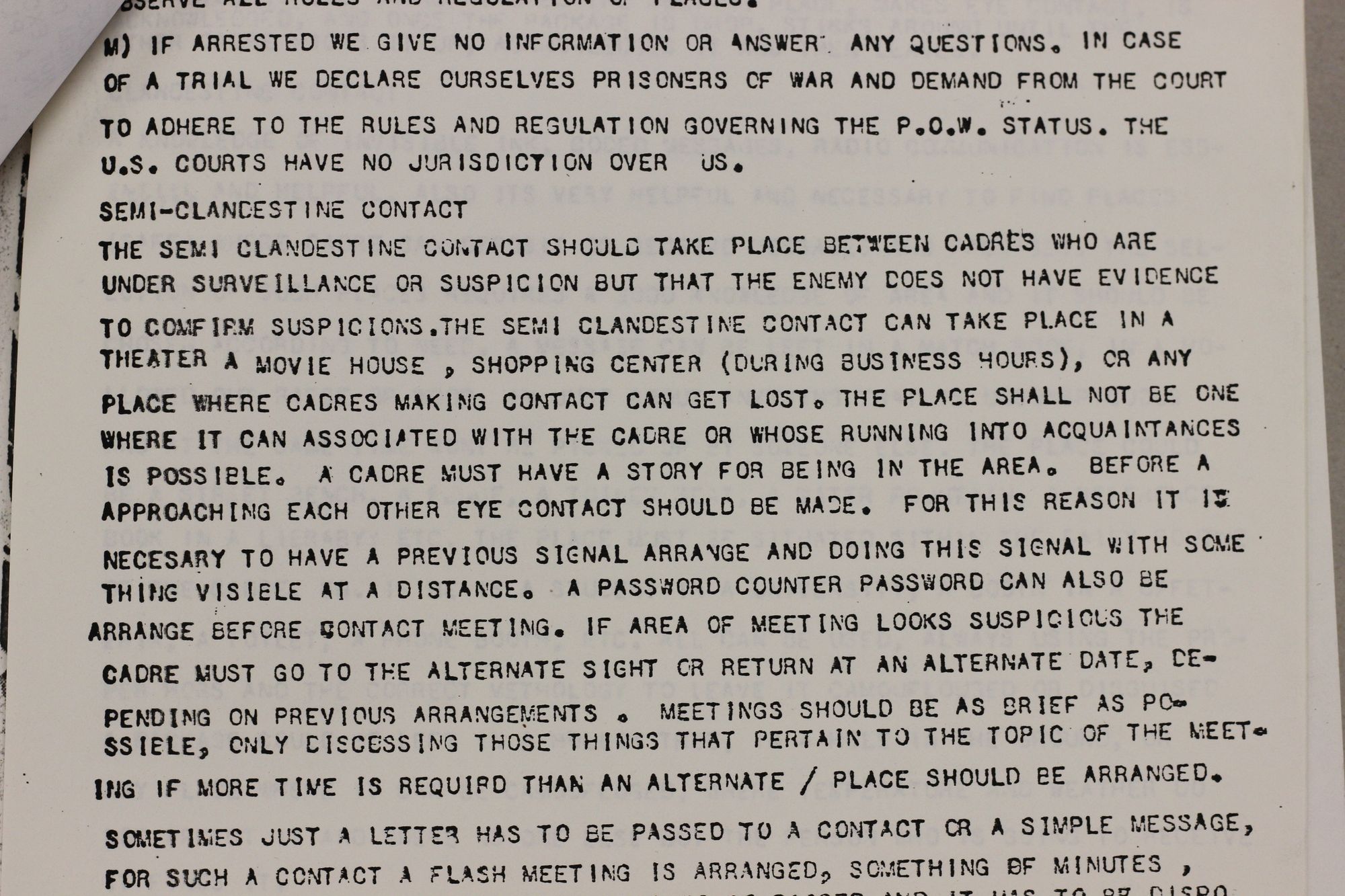

The FALN had well-documented links to Cuban intelligence, which provided support and training. Cuban intelligence officers, who had long punched above their weight, were themselves trained by the KGB. So the manual, titled “Security and the Cadre,” offers a rare peek into how an expertly trained clandestine organization instructs its operatives to work under hostile conditions.

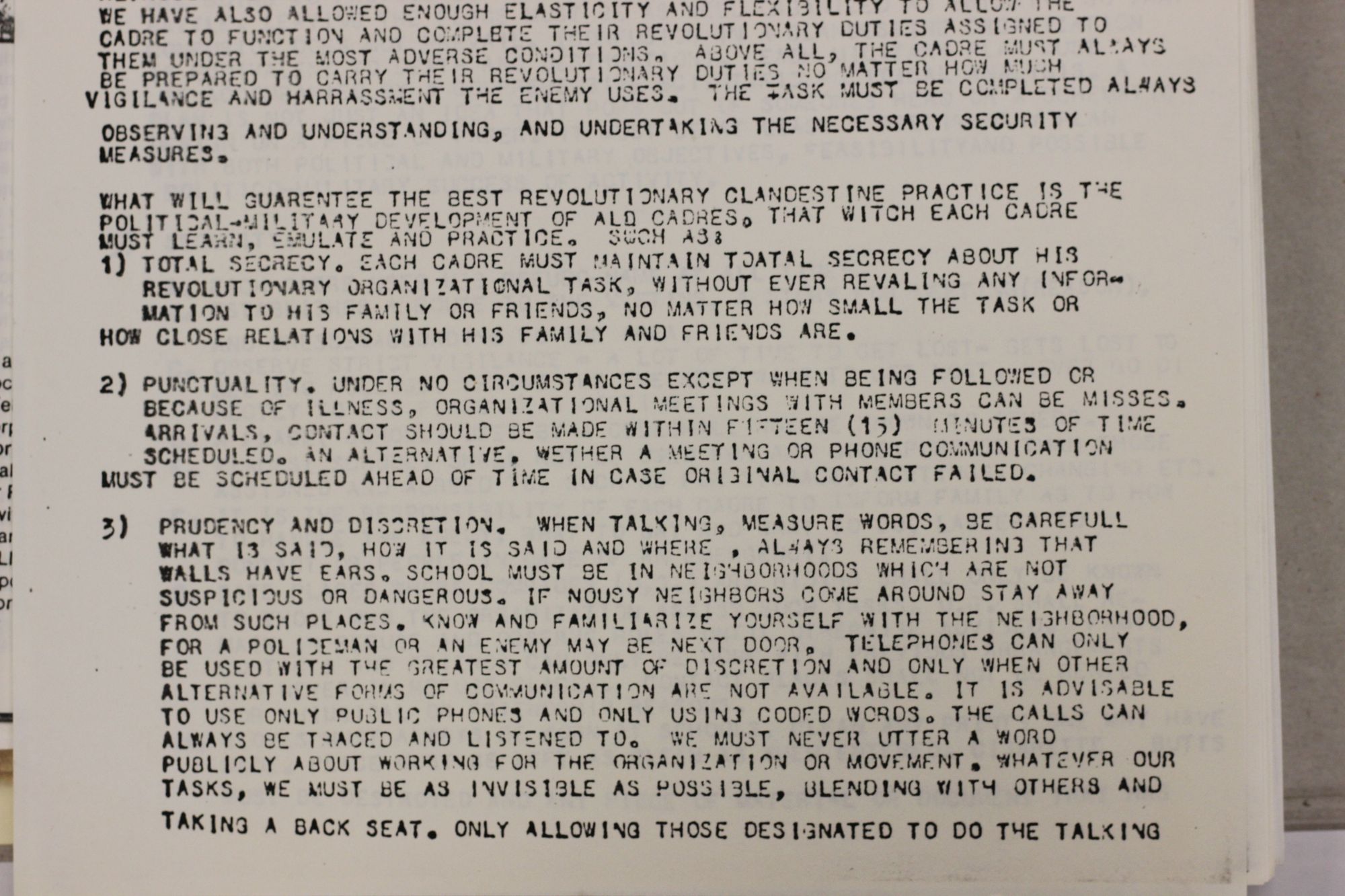

While some of the FALN guide is dated — “use only public phones and only using code words,” it says, regarding phone use — I suspect that much of it would read as pretty fresh to spy services and terrorist operators today. (Here’s another iteration of the same FALN manual; the copy I found at Hoover Institute appears to be an earlier, longer version, with more typos.)

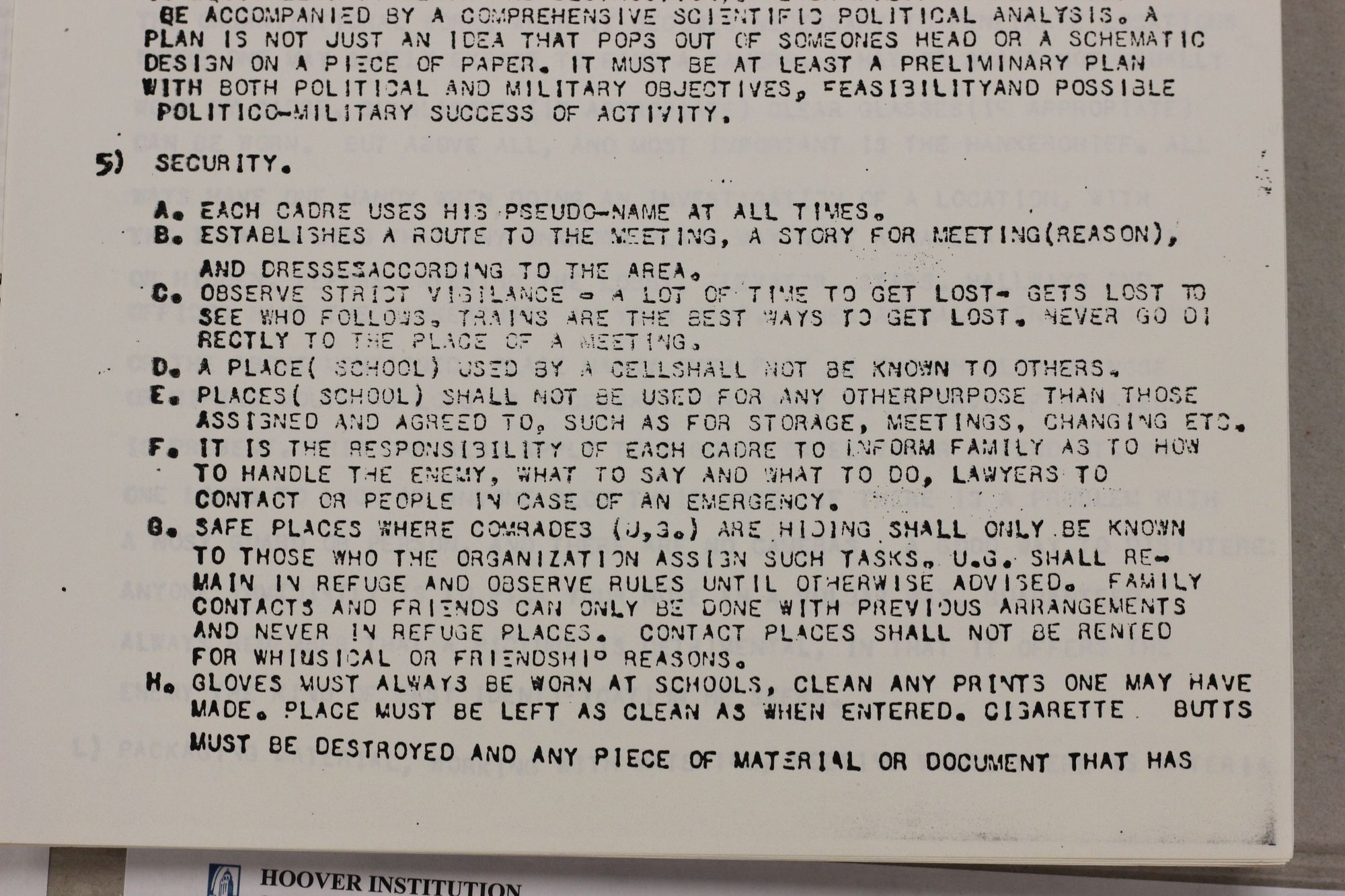

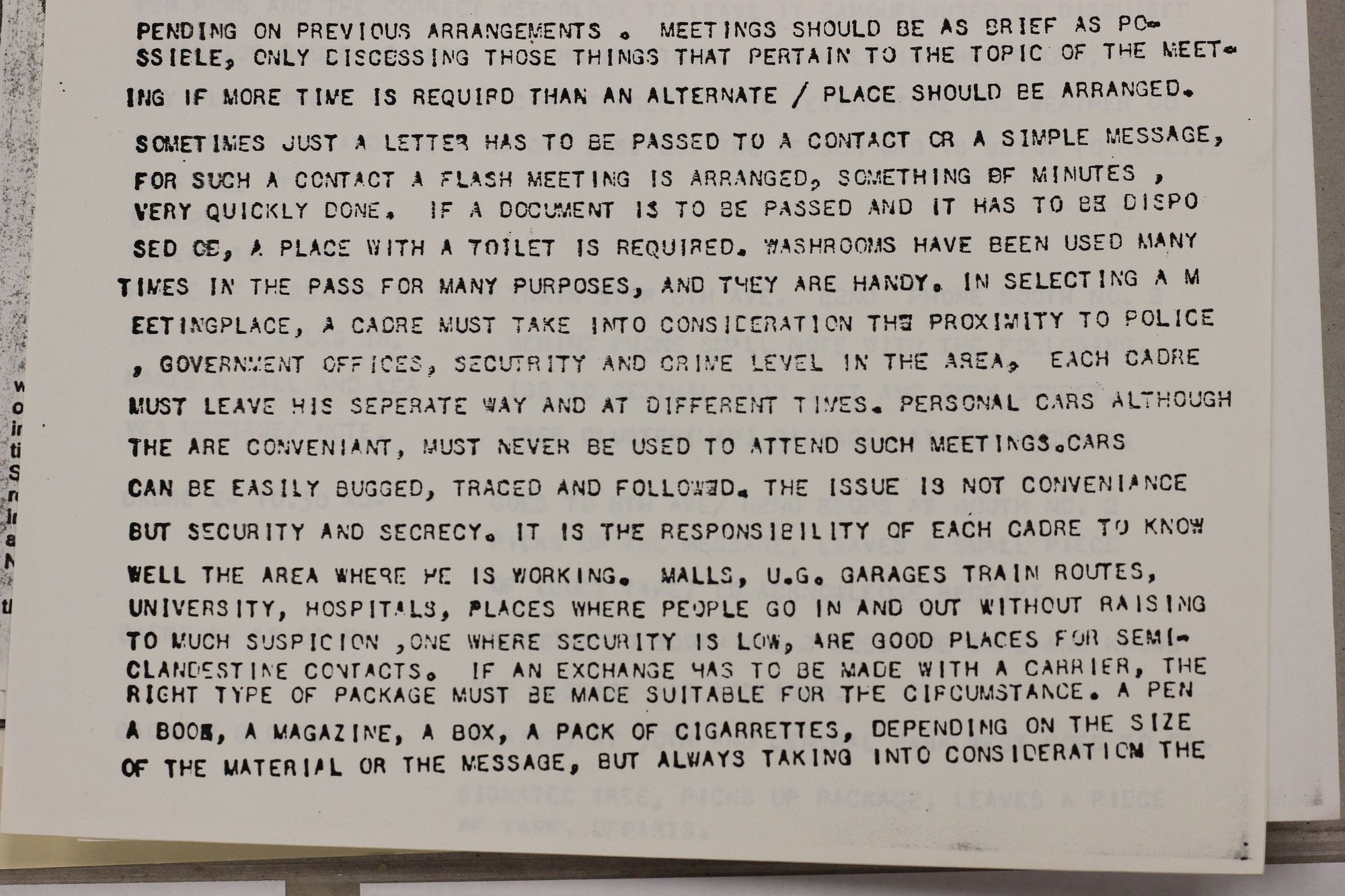

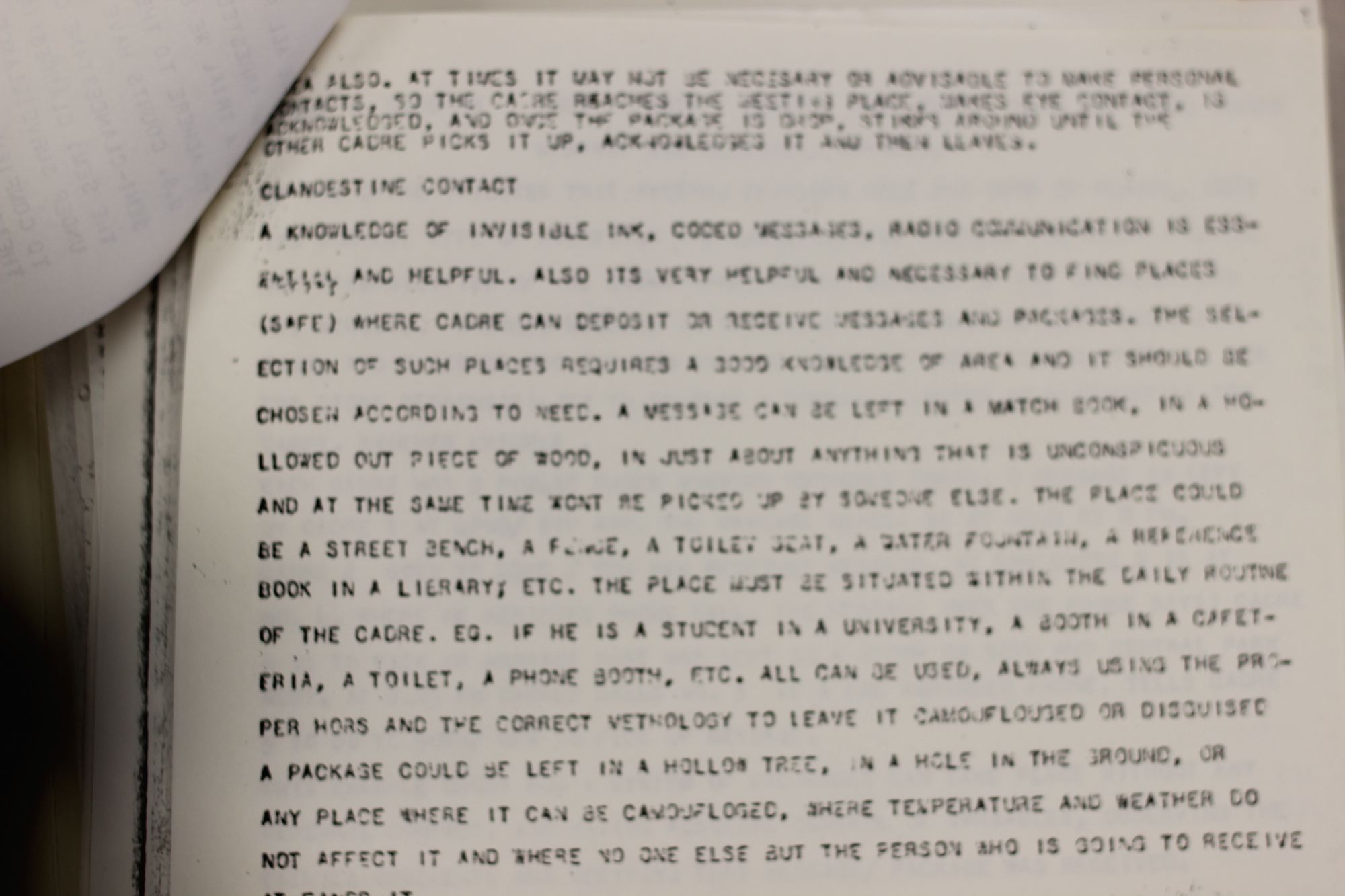

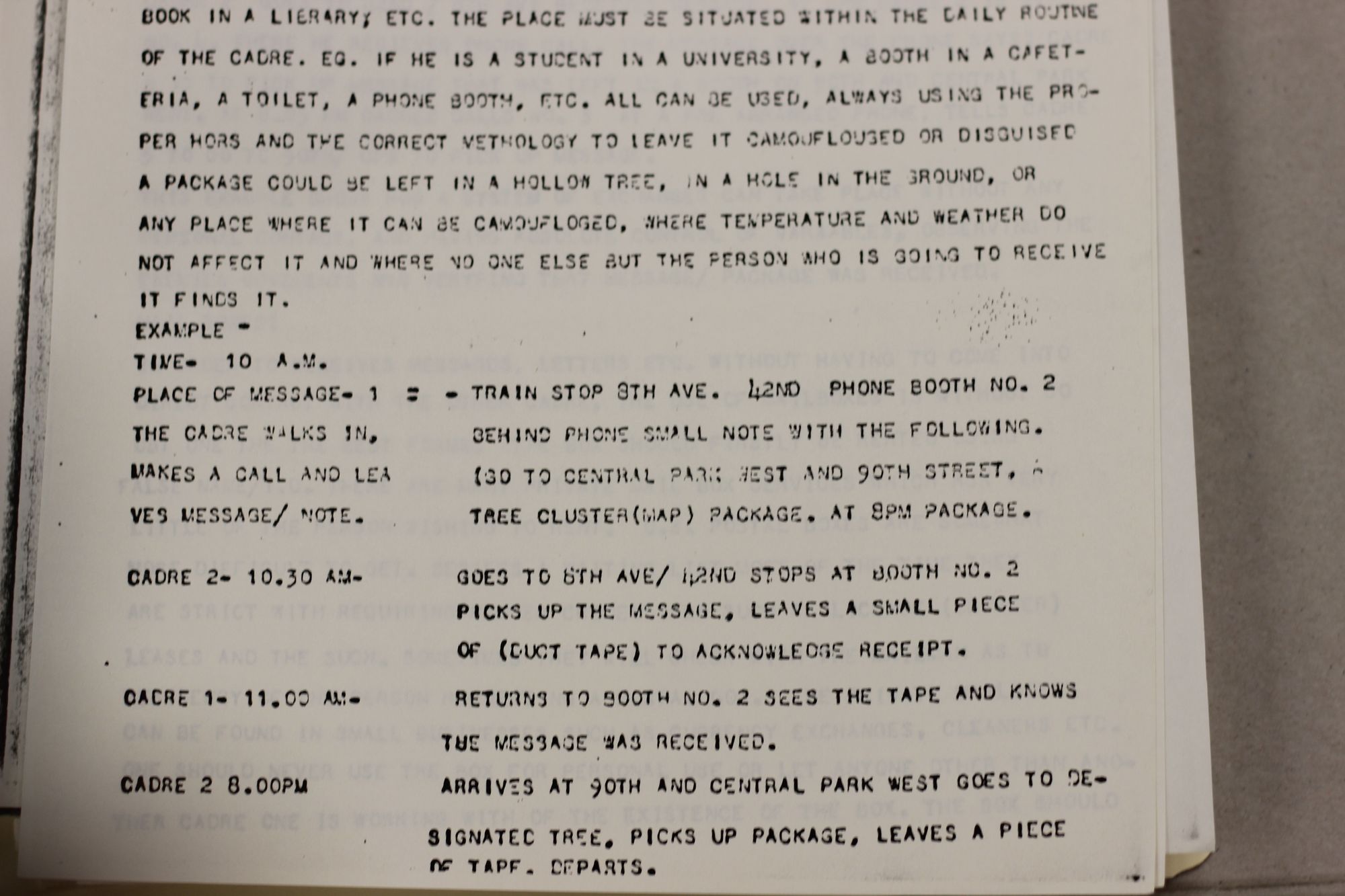

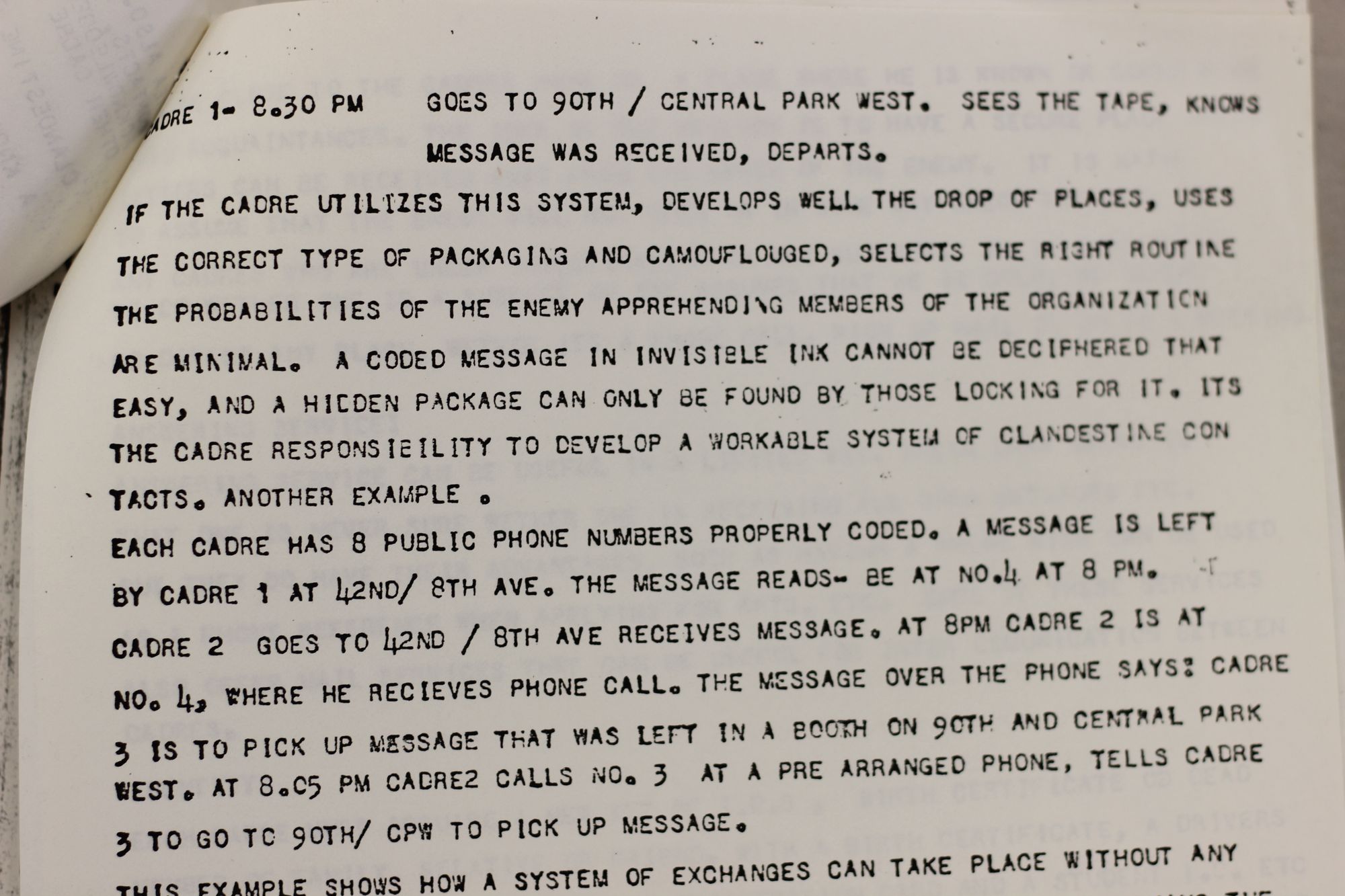

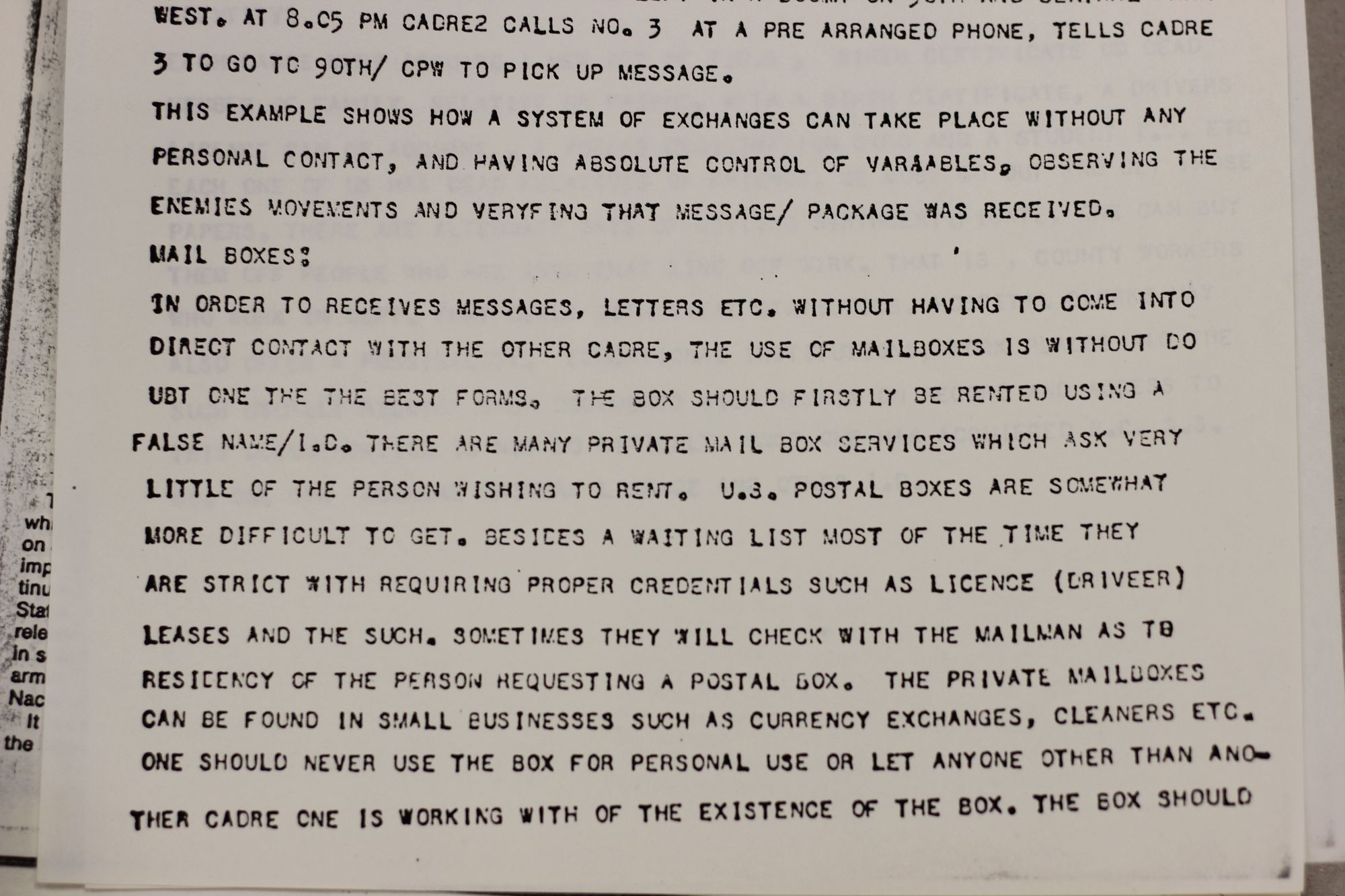

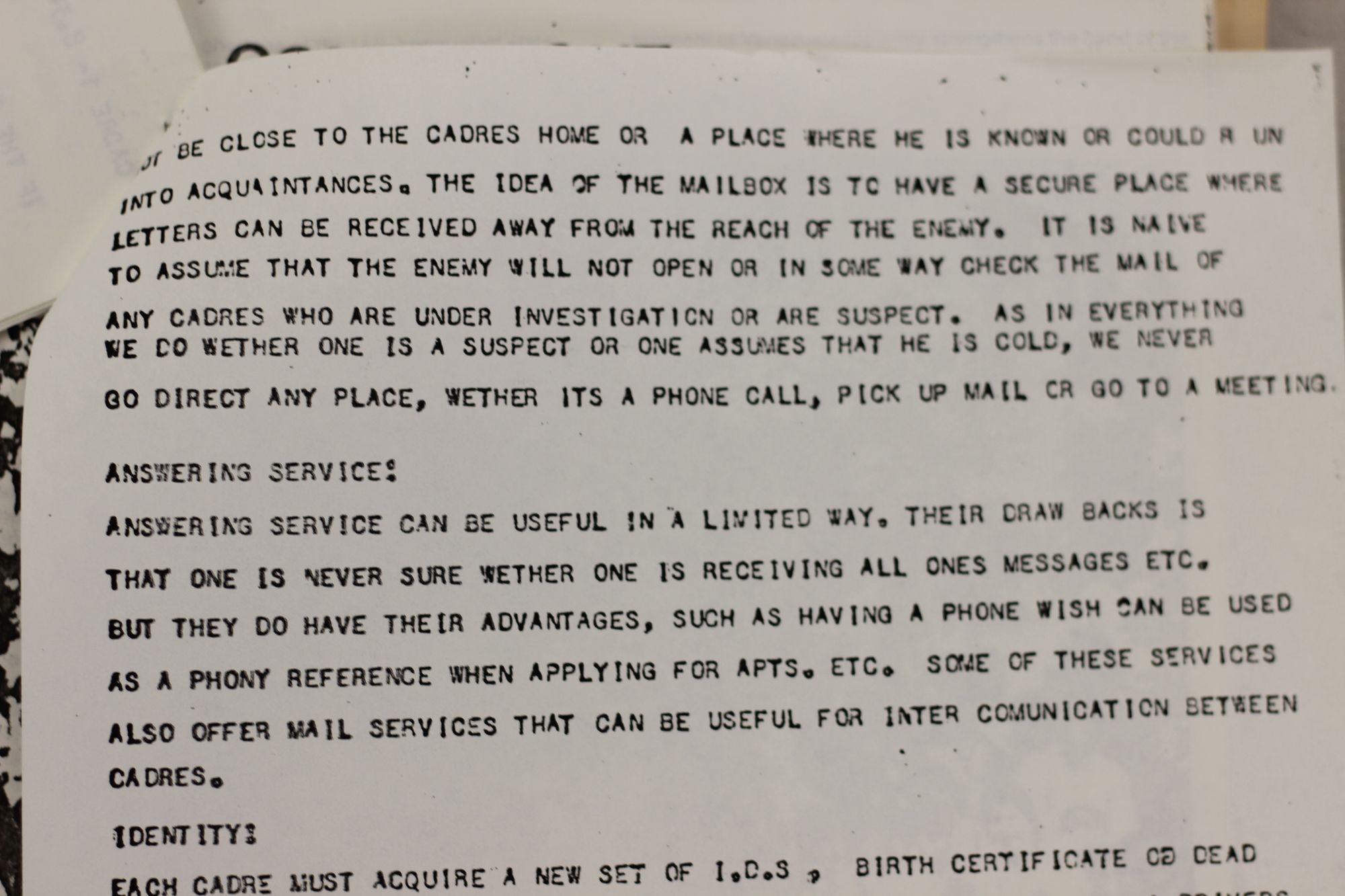

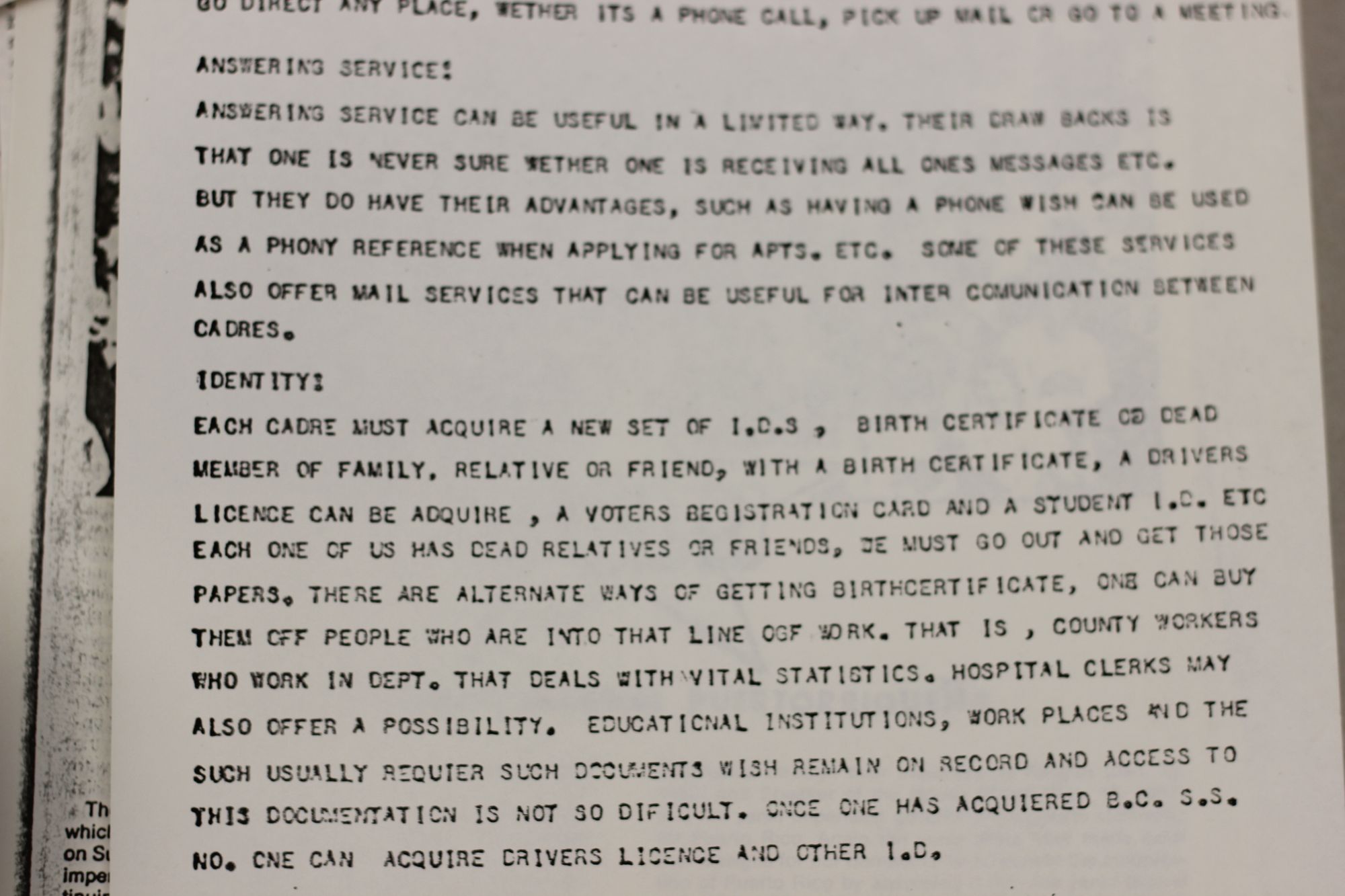

The manual features, among other things, a detailed passage on how to run dead drops between cells in New York to maintain secrecy about the organization, advice for where and how to pass messages, and sections on creating personas and obtaining fake identification papers. It offers also offers suggestions for obscuring your identity around security cameras (wipe your face with a handkerchief) and avoiding attention in public (tip: pick your nose grotesquely).

FALN endured for as long as it did while operating under hostile conditions precisely because it showed such discipline and benefited from top-tier training. “One must observe religiously the rules and regulations of security in order to protect the organization, its cadres, its secrets, its documents, arms, houses, and other instruments and work,” the guide says.

The FALN relied on core, low-tech, “sticks and bricks” tradecraft. Old-school die hards swear by this approach: It’s simple, time-tested, and neither officer nor agent ever need rely on newer, potentially insecure — or compromised — technology. For intelligence officers and particularly their agents, using bad tech can be a matter of life and death.

So even as twentieth-century communications infrastructure like pay phones are literally being ripped from the earth, “tradecraft” fundamentals appear surprisingly durable. Many memoirs by former intelligence officers extol their coursework at places like The Farm, the nickname for the CIA’s main Virginia training facility, and how they applied the skills they learned there in the field.

“Confusion in a clandestine organization is equivalent to death and destruction,” says the FALN guide. I’m sure, in this at least, intelligence officers from all over the world would agree. In a world of pay phones or iPhones, certain fundamental truths of espionage are self-evident.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.

Check out Project Brazen's new docuseries, HIDDEN WORLDS. The first episode looks at London's secret, private surveillance industry.