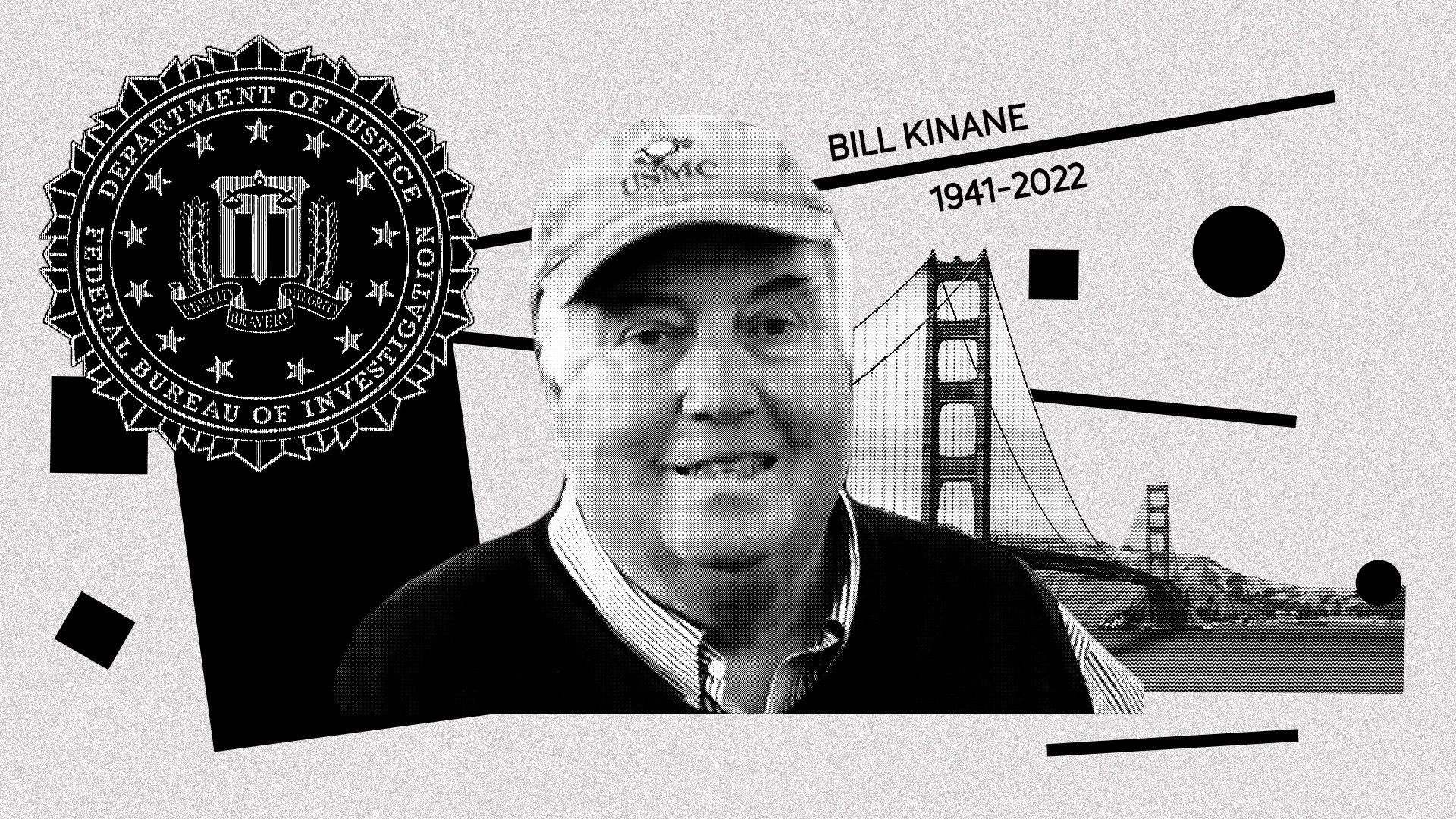

The counterintelligence life: a remembrance of FBI agent Bill Kinane

In 1998, amid the chaos and corruption of post-Soviet Russia, Galina Starovoytova, a popular pro-democracy legislator and dissident, was assassinated in her apartment building in St. Petersburg. Many suspected that she had been targeted for her outspoken liberal views.

Soon after the killing, Bill Kinane, an FBI legal attaché in Moscow at the time, received a call from Grigory Yavlinsky, the leader of the liberal Yabloko Party. Kinane had been in Moscow since 1994, serving as part of the first team of Bureau agents officially stationed there. (FBI attachés serve overseas as liaisons between the Bureau and their in-country counterparts.)

Yavlinsky asked Kinane to come down to Russia’s parliament, known as the Duma. "He didn't tell me what he was gonna talk about," Kinane recalled. "Maybe he figured the phone call was tapped."

Kinane accepted Yavlinsky’s invitation, mostly out of curiosity. When Kinane arrived, however, he was surprised to be led to a conference room. There, he found roughly a dozen Russian legislators seated around a large table. In front of the assembled lawmakers, Yavlinsky told Kinane that he had brought the FBI agent to the Duma to help solve the assassination of Starovoytova — a crime Yavlinsky blamed on the Communist Party – whose leader was also at the meeting, Kinane recalled.

“And [the party leader] says, ‘That's baloney. We didn't kill him. And we want the FBI to come to Russia and investigate this.’ Now, this is the head of the Communist Party. And he says, ‘Our police are totally corrupt and incompetent.’”

Yavlinsky, the top Russian liberal, then chimed in: He, too, wanted the FBI's help with the investigation, as did the leaders of the fascist party, the women’s rights party, and the conservationist party, all of whom voiced their support for FBI assistance. Their mistrust for their own police went so deep that they had come to their old adversary – the United States – for help to solve the murder, Kinane realized.

Like many stories Kinane shared with me over the years, the more I thought about this one, the more it amazed me: an FBI agent sitting around a table at the Duma with a liberal, a fascist, a communist, an environmentalist, and a feminist lawmaker, all of them begging for his help. (It's like the beginning of a great joke in search of a punchline.) And there’s Kinane: slightly bemused, incorrigibly inquisitive, and above all, totally sincere. "They're all sitting at the table, eating cookies and drinking tea, all saying the same thing," he told me. (A spokesman for Yavlinksy denied Kinane's account of the meeting, but did not provide further detail.)

On July 23rd, Bill passed away unexpectedly, and too soon, at the age of 80. Over long conversations at his favorite coffee shops in Marin County, north of San Francisco, I got to know the Brooklyn-bred Bureau veteran. Without fail, we'd often be interrupted by his friends and admirers in the community who wanted to chat with him.

I won’t pretend to know Bill better than I did. But I do know former FBI agents who formed close friendships with him, some for over 40 years. (And there was a whole other critical part of Bill’s life, as a devoted father and husband, that you should read about here.) His former colleagues from the Bureau would describe him as an “absent-minded professor”-type, and even this gentle ribbing was borne from affection. Bill was, to his core, a real mensch.

Bill spent the bulk of his 34-year FBI career in San Francisco. He worked Russian counterintelligence there for many years, and also led the Eastern Bloc squad. A bona fide expert spy hunter, he investigated critical Cold War-era espionage cases that he could recall in great detail decades later. His tenure in San Francisco coincided with some of the hottest periods of the Cold War, when the conflict between the the U.S. and Soviet Union often took on an existential cast, and the specter of nuclear conflict loomed over nearly everything. Whether it was to undertake high-tech theft, or spy on political eminences and domestic radicals, or make inroads into the local scientific and university communities, the Russians and their allies heavily targeted Silicon Valley and San Francisco, according to Bill and many other Cold War-era Bureau veterans I've met.

By the 1980s, Silicon Valley had already emerged as the world's leading center for technological innovation. And, then as now, the Bay Area was a political powerhouse, with many important players – figures of interest to foreign spies – cycling through San Francisco politics, as well as at positions at Berkeley and Stanford. Bill had a front-row seat to all that history.

Bill also had wild tales from his time in Moscow. He met Vladimir Putin. He visited the headquarters of the FSB, the Russian intelligence agency that is the main successor to the Soviet-era KGB. He worked with Russian police investigators to help solve a major early case of Russian cyber spying – until those same investigators told him they'd learned that Moscow’s own intelligence services were responsible for the hacking, and could assist the U.S. no longer.

As for the case of Galina Starovoytova, the assassinated lawmaker, at first Bill demurred at his meeting with the Russian legislators. The FBI couldn’t simply fly to Russia to take over an investigation in a foreign country, he told them. There were legal protocols and requirements to satisfy before the bureau could assist Moscow in any way.

But eventually, the Bureau did help identify the weapon used to kill Starovoytova, he recalled. In Russia, contract killers "leave everything behind: The gun, the hat, clubs, everything they wore, and run," he said. So the Russian authorities possessed the murder weapon, but the serial number had been shaved off.

The Russians sent the gun back to the FBI crime lab, where experts there managed to trace its origin to Croatia, according to Bill.

Over the course of our conversations, I came to see Bill as a de facto espionage historian – albeit one who had chased Russian intelligence officers, American nuclear spies, and Yugoslav terrorists across the Bay Area and beyond. A natural storyteller, he was steeped in the theory, and practice, of counterintelligence.

A former FBI agent and friend of Bill's recalled that, every morning, Bill would go to a coffee shop near the Bureau’s San Francisco office to read The New York Times. Some viewed this as a curiosity, a distraction from the work of spy-hunting. But I think Bill understood that counterintelligence requires the view from 10,000 feet, as well as an understanding of the details — that to know what spies are doing in your own backyard, you have to understand how the cogs of international and domestic politics are constantly turning.

Every time I met him for coffee, many years after he retired from the Bureau, he still had a copy of the Times in his hands. I count myself lucky for having had the opportunity to learn from him.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.