On Getting To Know An American Spy For Moscow's Proxies

James Harper was perhaps the most perplexing interview subject of my journalistic career.

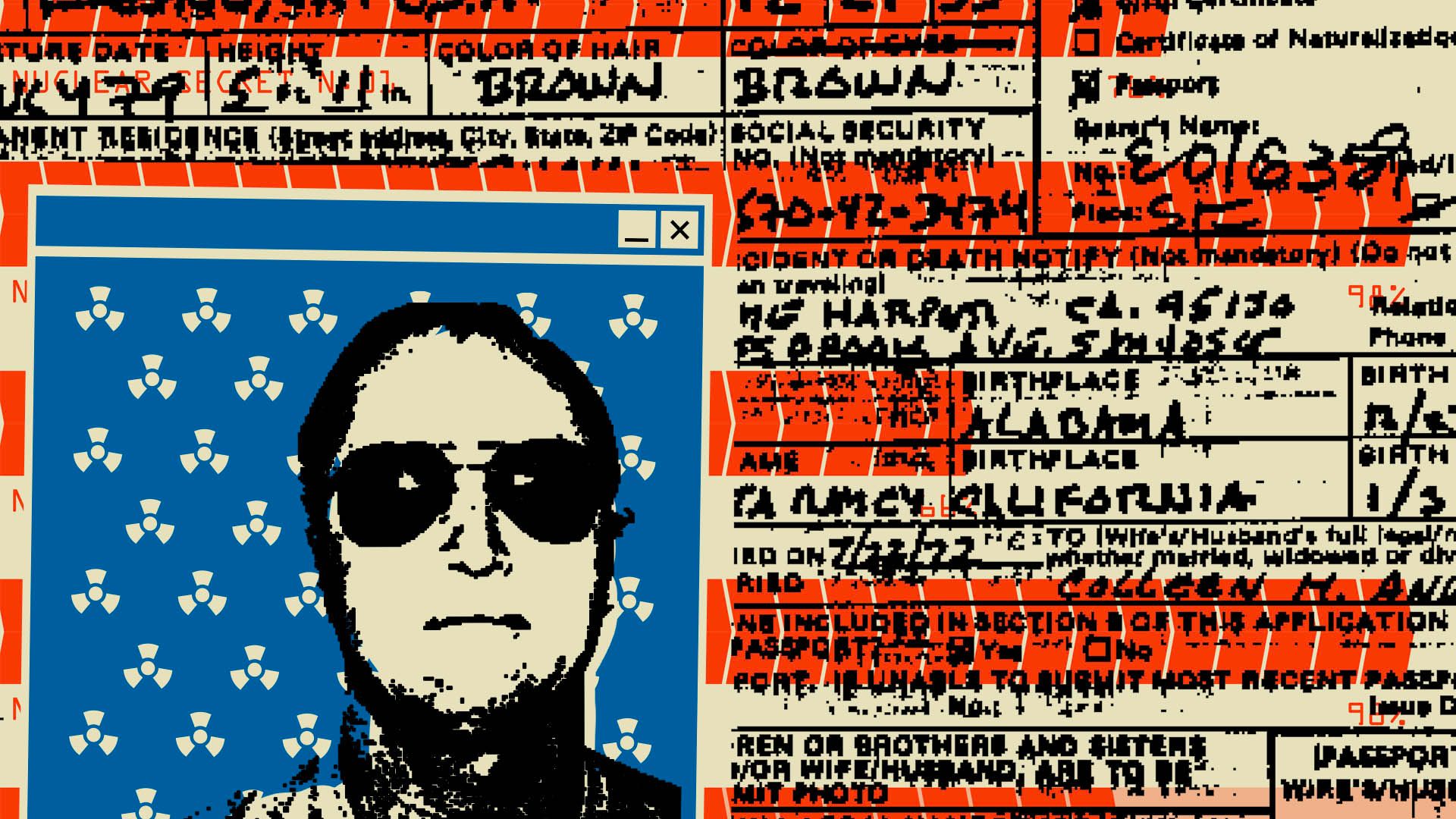

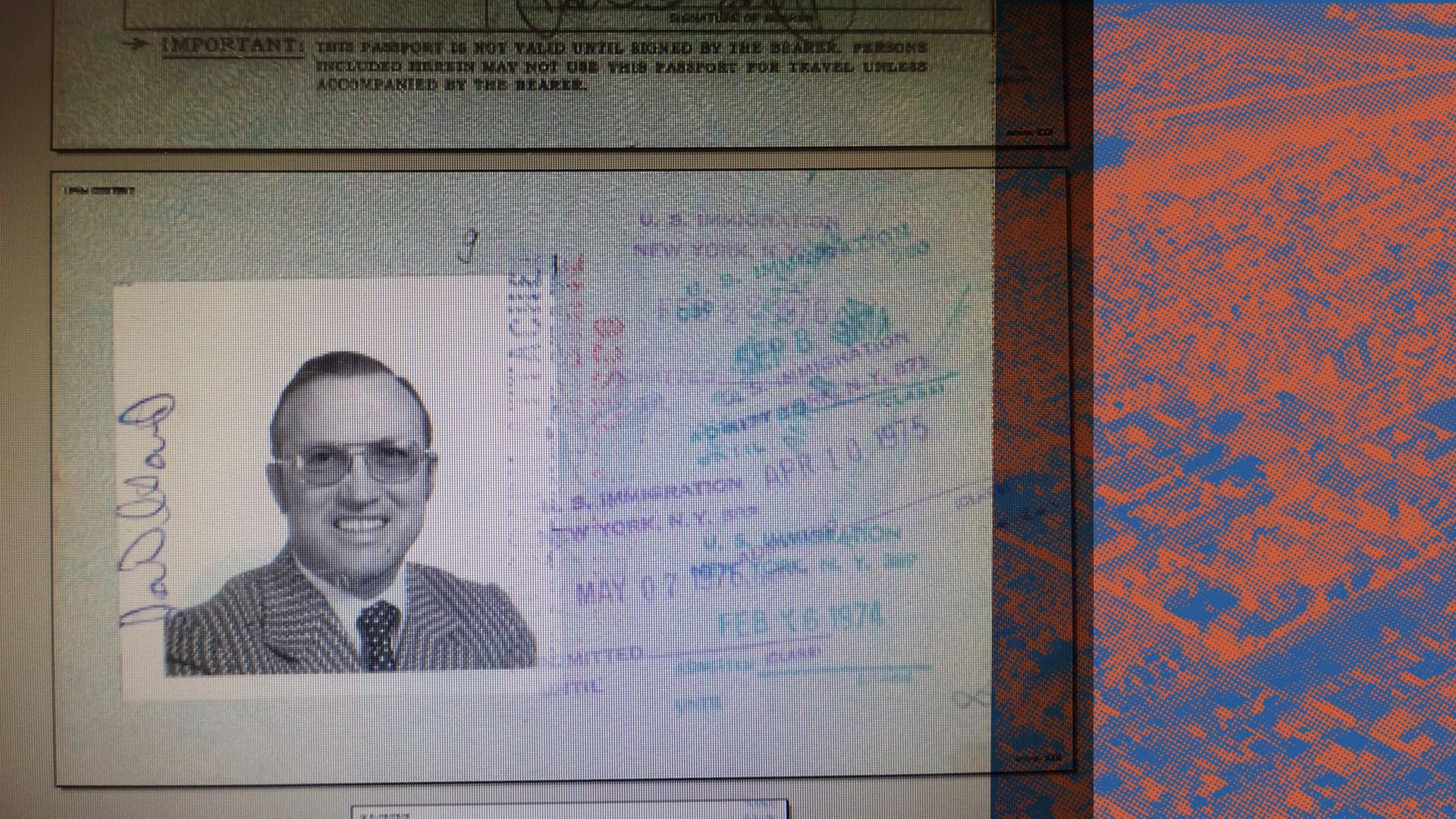

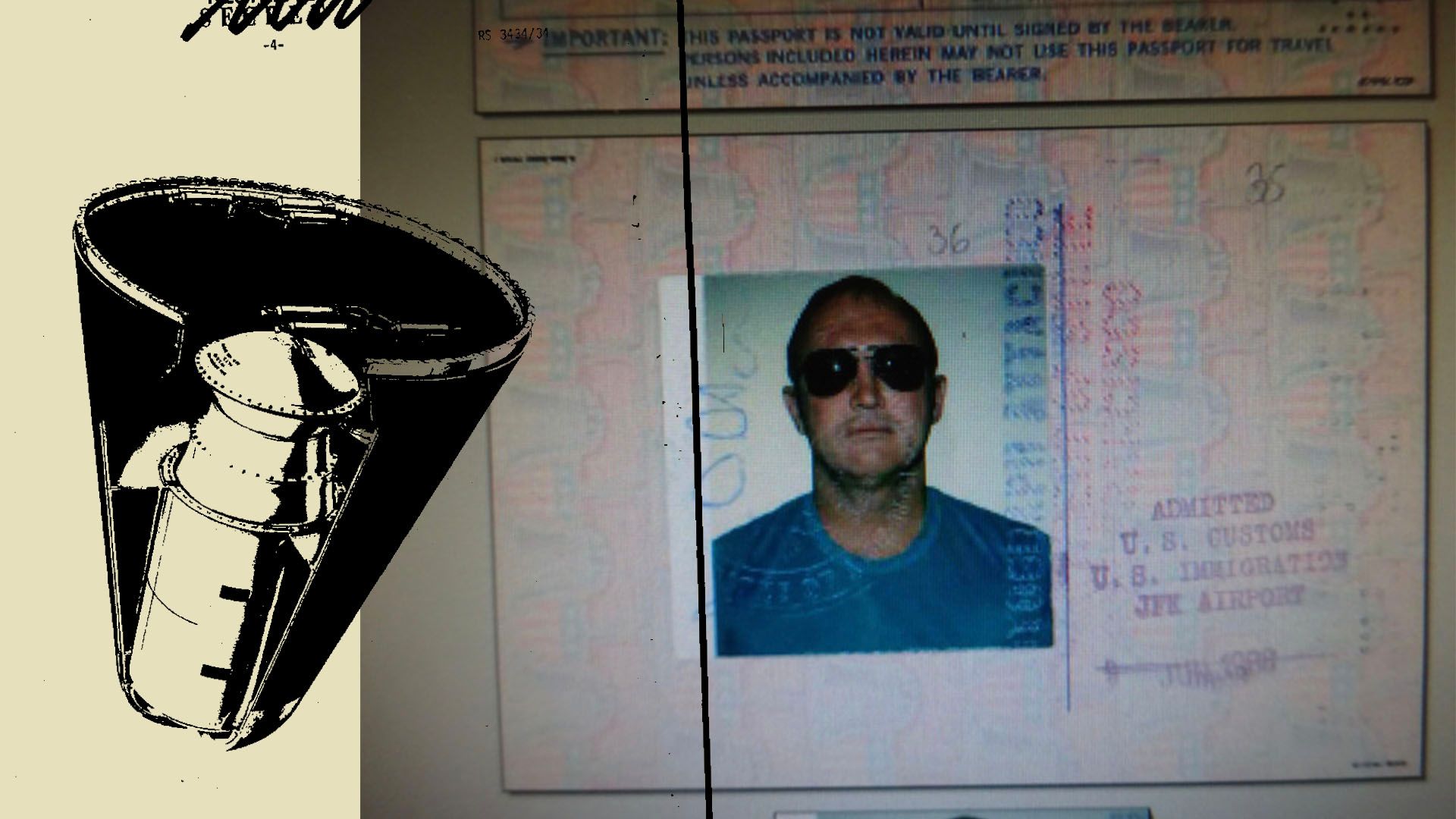

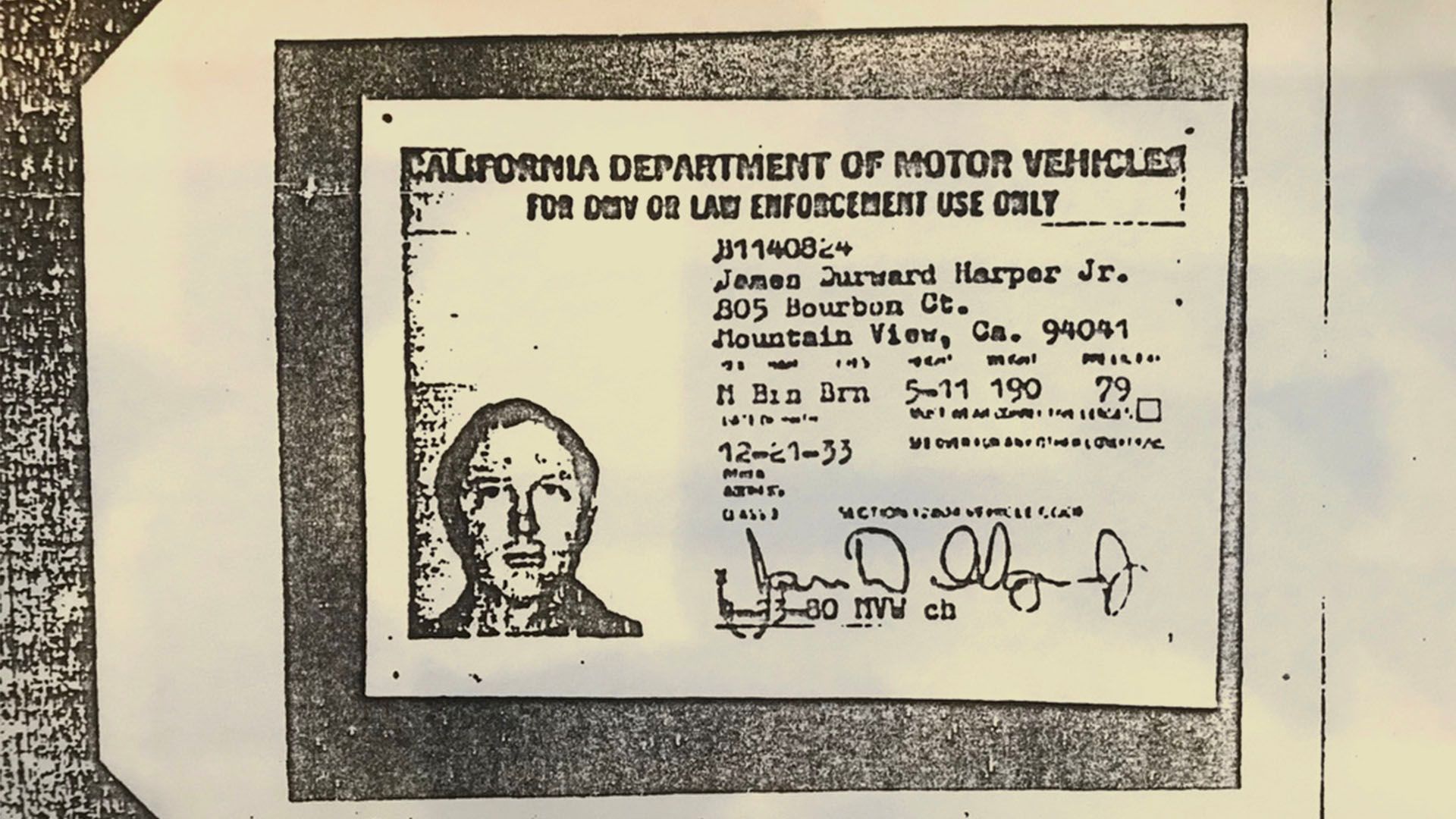

James Harper—the Silicon Valley-based Soviet Bloc turncoat at the heart of Spy Valley—was perhaps the most perplexing interview subject of my journalistic career.

You have to understand something about my line of work. I talk mostly with U.S. officials from within the intelligence and national security bureaucracy, the three-letter agencies like CIA and FBI. I’d like to think I have a reasonable grasp on that world, for someone who is, by necessity, an outsider. I know a good number of folks from that world, and have grown to admire more than a few. (The sentiment is not always reciprocated: that’s the job.)

But chatting it up with an actual ex-spy who worked against America, as an agent for Washington’s nemeses? That was a totally different sort of experience for me. Now, in rare cases, some U.S traitors have told their stories to the press: the notorious CIA officer-turned-Soviet-mole Aldrich Ames granted some interviews after his arrest in 1994; and Edward Lee Howard, a CIA turncoat who successfully escaped to Moscow, met with a prominent intelligence journalist in Budapest in the late 1980s.

But these are the exceptions that prove the rule. In general, ex-turncoats aren’t the chattiest bunch. Many are, well, imprisoned, serving long sentences. And when—if—they get out of incarceration, most seem to want to live quiet lives, away from the spotlight. I imagine it’s pretty unpleasant to relive the decisions that led to you passing secrets to America’s foes, and spending years, perhaps decades, in federal penitentiary as a result.

So I really had zero expectations that James Harper would speak with me, even after I managed to track him down. The brilliant suggestion to write Harper a letter in the mail came from Sharon Weinberger (now the Wall Street Journal’s national security editor). Sharon believed that a gentle outreach to Harper might work best, and that Harper (as a man in his mid-80s) would appreciate the older-fashioned approach.

And she was right. In our initial conversation, Harper remarked that he had been impressed that I took the time to write him a letter. (And it was a pretty long, and formal, one at that.)

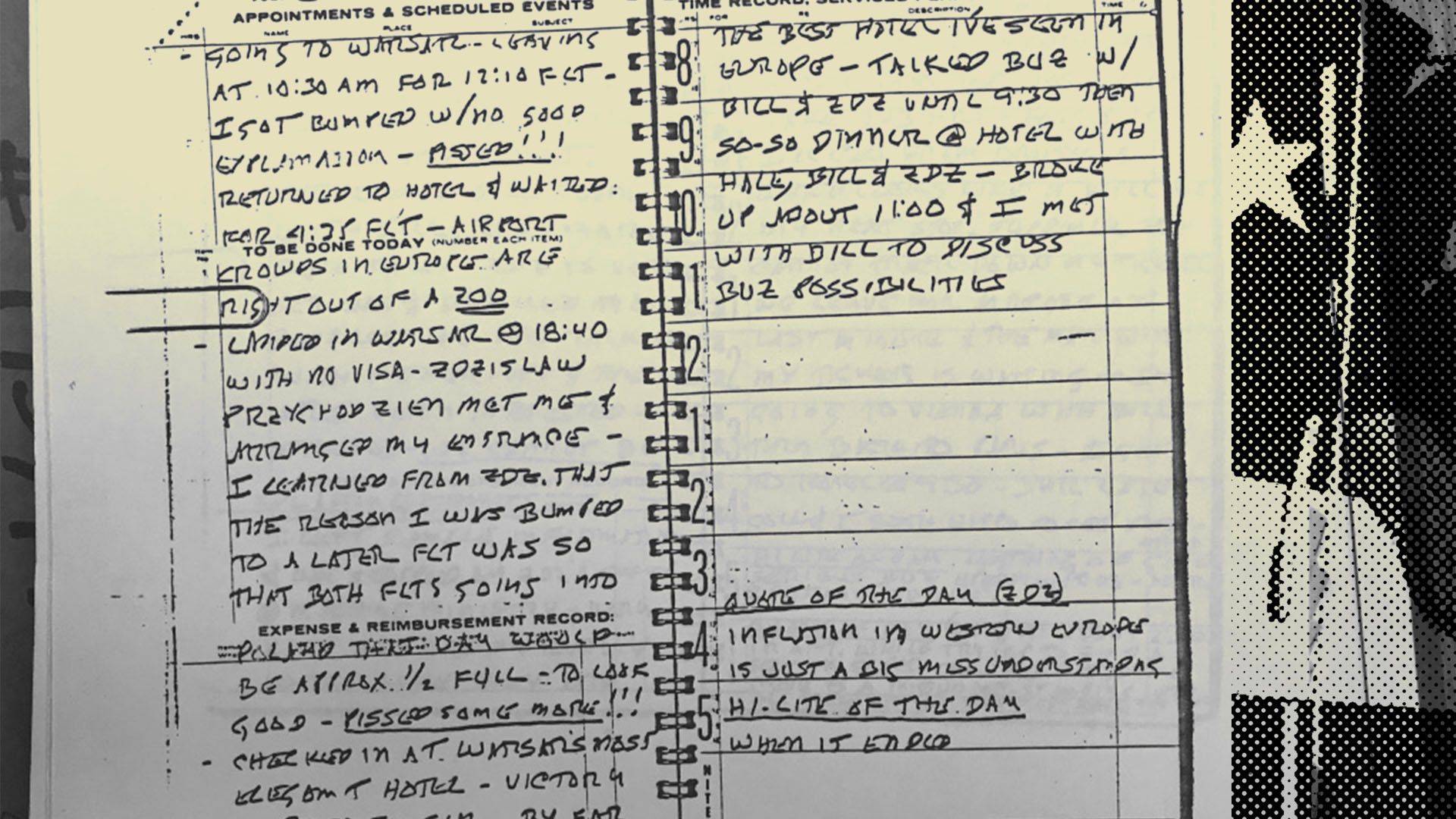

This set the tone for our relationship. Harper could be difficult to pin down—he’d call me randomly, revved up and ready to talk—then disappear for long stretches, not returning my calls. But, and I truly believe this, he was essentially honest with me about his life as a spy for the Eastern Bloc.

It took me a while to accept this fact. First, because journalists in general are a skeptical bunch. Trust, but verify. If your mother says she loves you, check it out. And so on.

Second, because I was predisposed not to trust him—he was a damn turncoat after all, a convicted spy who repeatedly betrayed everyone around him, up and down the chain from his family and friends, to his investors and business partners, to his country. So, no: I assumed, at first, that he would lie to me liberally.

But then something odd happened. As I gathered more and more material evidence about Harper’s spying—from thousands of pages of Polish intelligence files to huge stacks of FOIA’d documents on Harper’s case—I started being able to verify a lot of what Harper was telling me, that wasn’t already public.

And he was. . . speaking the truth, or something approximating it, given the vagaries of memory. Generally, though he was on the money.

Did Harper omit details that probably painted him in a bad light? Sure. But he was surprisingly blunt about his spying, his drinking, his philandering, his gambling. It was all just . . . matter of fact. He didn’t seem to be judging himself for his past behavior, or have any remorse about it. Sometimes it seemed like he had a kind of mechanical view of his own past treachery.

This might have made him a bad man, but it made him a great interview.

Reporters, naturally, have an affinity for people who like speaking with them. And they have an even greater affinity for people who tell them the truth. (It’s not illegal to lie to reporters, but we have memories like elephants for those sorts of things.)

So this, for me at least, was a unique situation. I had a subject who had done the unthinkable, who was (as far as I could tell) unremorseful about his actions—and who was now answering my nitpicking queries with shocking candor.

These things were probably related. To look dispassionately upon your own life like that—particularly when it was defined by so much obvious wrongdoing—probably requires an unusual store of amorality. Or worse.

We can condemn somebody while also seeking to understand them. James Harper did terrible things, and he spent over 30 years—a lifetime, really—in federal prison as a result. I’d like to think, though, that by sharing his tale of treachery and espionage so fulsomely with me, Harper’s story can provide useful lessons, and a rich character study, for those of us invested in the world of intelligence and national security.

That this could be one decent thing that trails the ruin that Harper left in his wake.

Listen to the first episode of Spy Valley: An Engineer's Nuclear Betrayal

Silicon Valley is an espionage innovator—and it has been since its inception. Journalist Zach Dorfman uncovers how Moscow’s spies opened up shop in San Francisco and Silicon Valley at the dawn of the hi-tech age, and how a group of pioneering FBI spy hunters assembled to stop them—and solve the case of a lifetime.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.