On the Mystery of “Caribou,” the CIA’s Secret Agent in Polish Intelligence

While reporting Spy Valley, my six-part podcast on the case of Silicon Valley-based nuclear spy James Harper, there were some key folks with whom I wanted to talk, but for various reasons, couldn’t. Retired FBI agents. Ex-CIA officers. Old Silicon Valley bigwigs.

But there was no spectral presence who loomed larger over the story than the man the FBI codenamed “Caribou.”

Caribou was a secret CIA mole within the communist-era Polish intelligence service. The Polish spy first came to the attention of the FBI in the early 1970s, when he was stationed, under diplomatic cover, at the Polish Consulate in Chicago. He was eventually recruited by U.S. intelligence and rotated back to a new job in Warsaw. From his perch in Poland, Caribou secretly provided U.S. intelligence critical information about the man the Bureau would eventually identify as James Harper.

Caribou’s story is worthy of a podcast or book of its own. There was a lot about him we simply couldn’t fit into the show. But, after years spent reporting this story, I can say with confidence that Caribou was–quietly–one of the most consequential CIA penetrations of an opposing intelligence service during the later Cold War.

On the Mount Rushmore of Cold War-era, U.S. spies from the Soviet Bloc–like Penkovsky, Tolkachev, Polyakov, or Kukliński–Caribou’s name is nowhere to be found. But it probably should be.

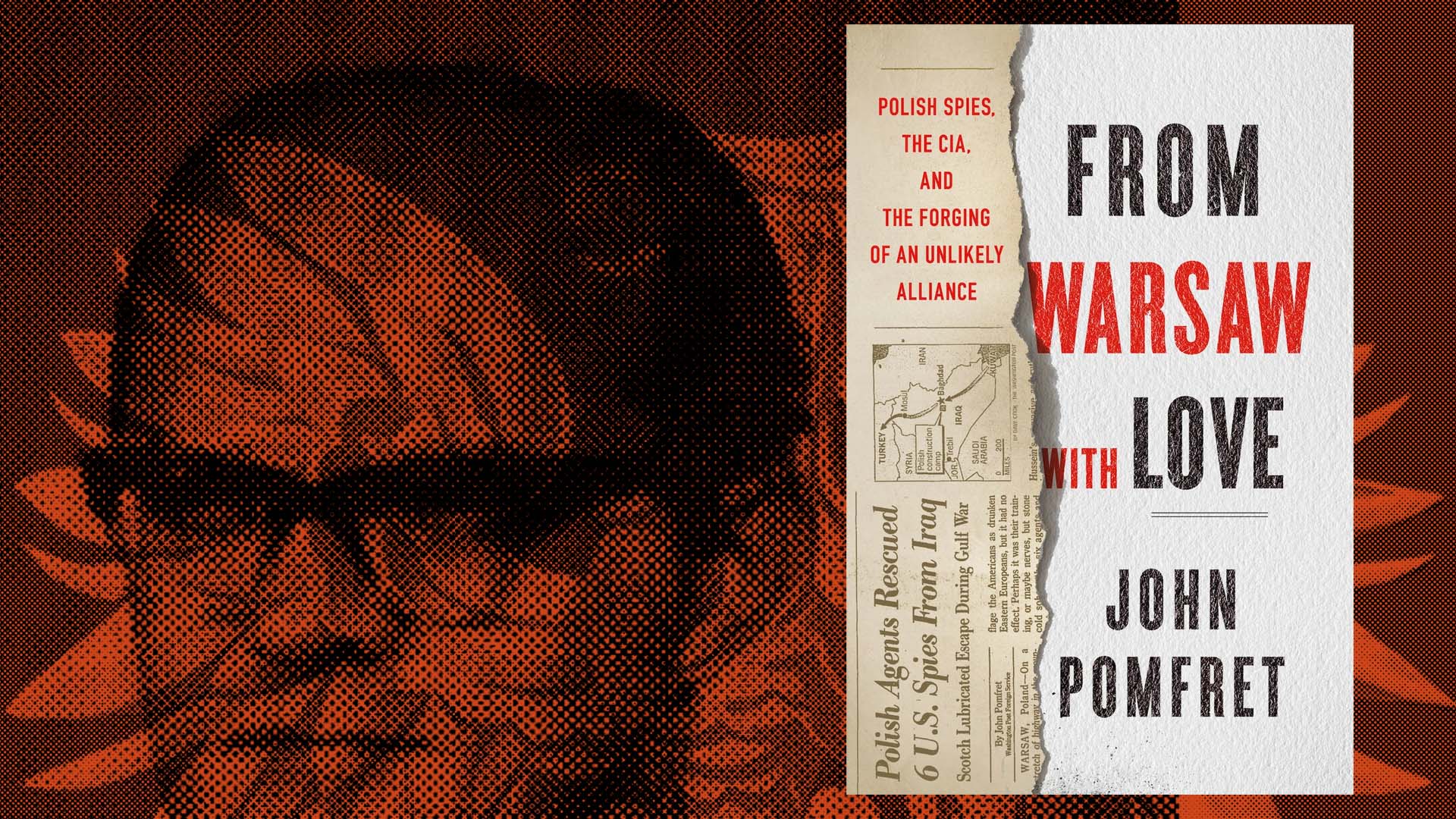

You don’t have to just take my word for it. In From Warsaw With Love, his thoroughly reported book on the history of the U.S.-Polish intelligence relationship, John Pomfret identifies Caribou as the secret CIA source who led to the discovery and arrest of Marian Zacharski, a deep-cover Polish intelligence officer based in Los Angeles who was arrested in 1981 for stealing classified defense secrets. It was a huge case in its day.

Bill Kinane, a former top San Francisco-based FBI spyhunter, also told me Caribou gave the Bureau the leads for at least a handful of other major cases. And in the Poles’ own declassified communist-era intelligence archives, Polish spooks assessed that Caribou’s own defection to the West would cause “incalculable losses” to Warsaw’s spying efforts, especially in science and technology.

But, again, Caribou–whose real name was Jerzy Korycinski–is still almost entirely unknown to this day.

Given the historical import of his work, that should be remedied. The following biographical sketch is based on his voluminous, totally unredacted, file from the declassified Polish intelligence archives.

Caribou, or Korycinski, was an engineer by trade, with a post-graduate degree, an educated man. He had a family—his wife, Halina, was also a highly-trained engineer—and two children, a son and a daughter.

According to his Polish intelligence file, he was recruited by the Polish spy services in 1964, while working for a giant state-owned tech conglomerate. He spoke English, Russian, and German. He was a quiet, bespectacled, private man. He had a rich family life but was not particularly friendly with colleagues.

American intelligence called him Caribou, but the Polish spy services codenamed him “Belski.” Later–and it’s not clear if the Polish services were aware of the irony here–they codenamed him “Mole.”

Korycinski served as an undercover intelligence officer in Turkey, posing as a trade attache, and then worked for a few fateful years in Chicago, when the FBI began to recruit him. While the Korycinskis were in Chicago, Halina took a job with some local U.S. government agency–a fact that Polish investigators would later point to as evidence of the family’s perfidy.

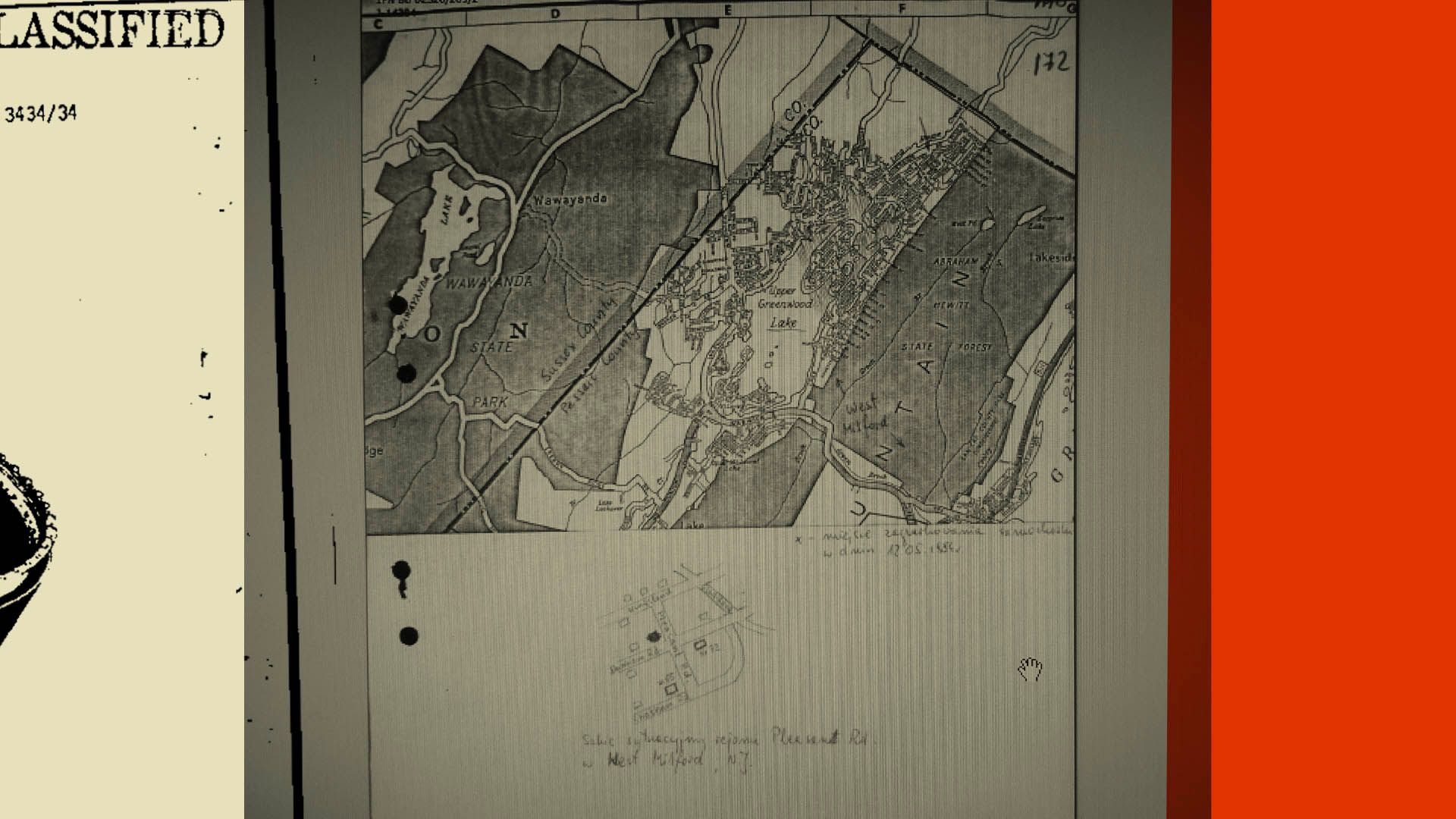

Rotating back to Warsaw in the mid-1970s, Korycinski operated out of the same science and technology-focused spy unit as a senior Polish intelligence officer named Zdzislaw Przychodzień, who ran the Harper case. That’s how he was able to pass on information about it to U.S. intelligence.

In late 1980, Korycinski left Poland to serve as a trade attache in Stockholm, Sweden—again, as an undercover intelligence officer. Korycinski ran agents there, and collected information on hi-tech, particularly with military applications. The whole family joined Korycinski in Sweden, with the two children enrolling in university classes there. This was key, because it meant that they were all outside of the Eastern Bloc when it came time to defect to the West.

In mid-1983, Korycinski—at this point, secretly spying for U.S. intelligence for years—received his new marching orders from his Polish superiors: he was to return to Warsaw for his next assignment. He was apparently visibly dismayed by the news.

Then, that August, days before his scheduled return to the Polish capital, over a summer holiday with his family in Sweden, the Korycinskis . . . disappeared.

At first, Korycinski’s fellow undercover Polish spies in Stockholm and Warsaw urged caution. Maybe the Korycinskis had been in some sort of accident. Maybe he was being held, incommunicado, by the Swedish security services. Korycinski was not known to take his duties particularly seriously, speculated one colleague. Maybe he had extended his vacation a few days without telling his superiors.

Maybe, maybe, maybe.

But soon enough, Korycinki’s fellow Polish spies began to contemplate whether he had defected to the West.

“There is an atmosphere of excitement in his office” over Korycinski’s disappearance, reported one. But “the worst scenario is possible,” wrote this spook.

Days passed. Korycinski was still in the wind. Anxieties mounted. At first, the spy bosses in Warsaw urged patience to their colleagues in Stockholm. “Despite the apparent danger, act calmly, carefully, be a calming presence for the leadership of the station,” wrote one official back to Stockholm.

A Polish official visited the Swedish ambassador in Warsaw to inquire about Korycinski’s status. Maybe they knew of his whereabouts? The ambassador professed to know nothing; reminding his communist interlocutor that Sweden was a free country, with freedom of movement.

Soon enough, Polish spies in Stockholm broke into the Korycinskis apartment. All the furniture had been sold. The TV was gone. All that was left was some winter clothing, underwear…and empty suitcases.

If they weren’t sure before, it was crystal clear now: Korycinski—along with his family—had betrayed the Soviet Bloc, for the West. The Polish spy services surveilled his apartment in Stockholm. Back in Poland, they tapped the phone lines of all the Korycinski’s relatives.

The knives came out. Korycinski was painted in Polish spy files as greedy, anti-social, and lazy.

“He was a typical malcontent, always unhappy with something. We think his desertion was his wife’s influence. Money had to be the reason” for his defection, wrote one ex-colleague.

Korycinski was denounced for his “uncommunicativeness, introversion, and disregard for co-workers. . . His official work was frequently criticized by his co-workers and the party.” He was “unengaged, and without ingenuity and necessary initiative.” He was “a typical penny pincher.”

And the Poles were pretty sure that—if Korycinski had turned to anyone—it was the CIA.

“Based on our knowledge of the methods of foreign intelligence services, it should be assumed that Korycinski’s desertion was prepared and carried out by the CIA outpost in Sweden,” they assessed. “It should be concluded that a foreign intelligence service equipped the Kroycinskis in falsified passports and clandestinely organized their departure.”

For the Polish spy services, denial gave way to anger, and finally, action. Every Polish intelligence officer in Sweden and Denmark was instructed to search for Koycinski—to pore over every contact he or his family members may have had, and try and retrace the steps he made before defecting.

The Korycinskis’ passports were held at the Polish embassy in Stockholm, and the missing spy wouldn’t have dared ask for them in order to undertake suspicious travel. So, asked his pursuers, did they drive over the Norwegian or Danish border to make their escape? Or perhaps take a ferry to a Finnish Island? Or catch flights under assumed names?

Soon enough, the Poles concluded that the Korycinskis had rendezvoused with the CIA in West Germany—and flew on from there to start their new life in America.

As revealed in Spy Valley, Korycinski did indeed make it to the U.S. with his family. He was subject to long debriefings by U.S. intelligence–standard for any defector–in the Washington, D.C., area. But Korycinski's defection was unusual, as federal prosecutors for the Harper case fully expected Korycinski to take the stand, in his own name, to testify during Harper's forthcoming trial. Korycinski's testimony was thought critical for putting Harper away.

But that never happened. According to Justice Department officials, the CIA reneged on its earlier promise to cooperate with the prosecutors on the case, who then scrambled to push Harper into taking a plea deal. Harper, who did eventually plead guilty, never found out just how worried prosecutors were about taking the case to trial without Caribou as a witness.

Then, like so many CIA defectors who are resettled stateside, Korycinski and his family disappeared into the ether. I tried to locate him for this podcast, but was unsuccessful. I don’t know if this important Polish ex-spy is even alive; if he is, he’s in his 80s or 90s. (He has different birth dates listed in his files.)

I asked the CIA if it could arrange an interview with Korycinski, or even just tell me if he was still alive–anything. The agency declined to comment.

Listen to the special bonus episode of Spy Valley: An Engineer's Nuclear Betrayal

The man codenamed “Caribou” plays a critical role in James Harper’s story, but his own story remains in the shadows. In this bonus episode, Spy Valley host Zach Dorfman sits down with Hanna Kozlowska, journalist and translator of the Polish archives used in the series, to discuss Caribou’s position as a mole for the US within the Polish spy service—and what happened when the Poles found out about his double-cross.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.