The Silicon Valley Spy Who Was As American As Apple Pie

While reporting Spy Valley, I was amazed at how tightly James Harper’s life story was intertwined with the evolution of the cold war—and the birth of Silicon Valley.

While reporting Spy Valley, I was amazed at how tightly James Harper’s life story was intertwined with the evolution of the cold war—and the birth of Silicon Valley. His story seems to capture something elemental about the promise, and peril, of America’s postwar years.

This future spy. . . was American as apple pie.

While his parents apparently had some marital troubles, Harper adolescence in the Bay Area during the late 1940s and early 1950s was pretty typical. He was jock, playing football and basketball, and running track. He loved muscle cars. He was a bit of a wild child, but had a natural genius for science and engineering. He happened to be from a part of the world where those precise skills would soon catapult many into enormous wealth.

In the early 1950s, Harper thought he was going to have to fight in the Korean War, but managed to ride the conflict out comfortably stateside as a Marine Corp engineer. His childhood was defined by World War II, his adolescence by Korea. Now, his adulthood would be defined by the dangerous nuclear “peace” of the cold war.

So here was James Harper: a young guy with a few years’ experience in the Marine Corps, and a natural talent for electronics, looking for work in his native California. And he first found it down in Los Angeles, designing rockets for a company that contracted with the U.S. military to design intercontinental ballistic missiles—missiles that could be equipped with nuclear warheads, and travel hallway across the globe to Moscow.

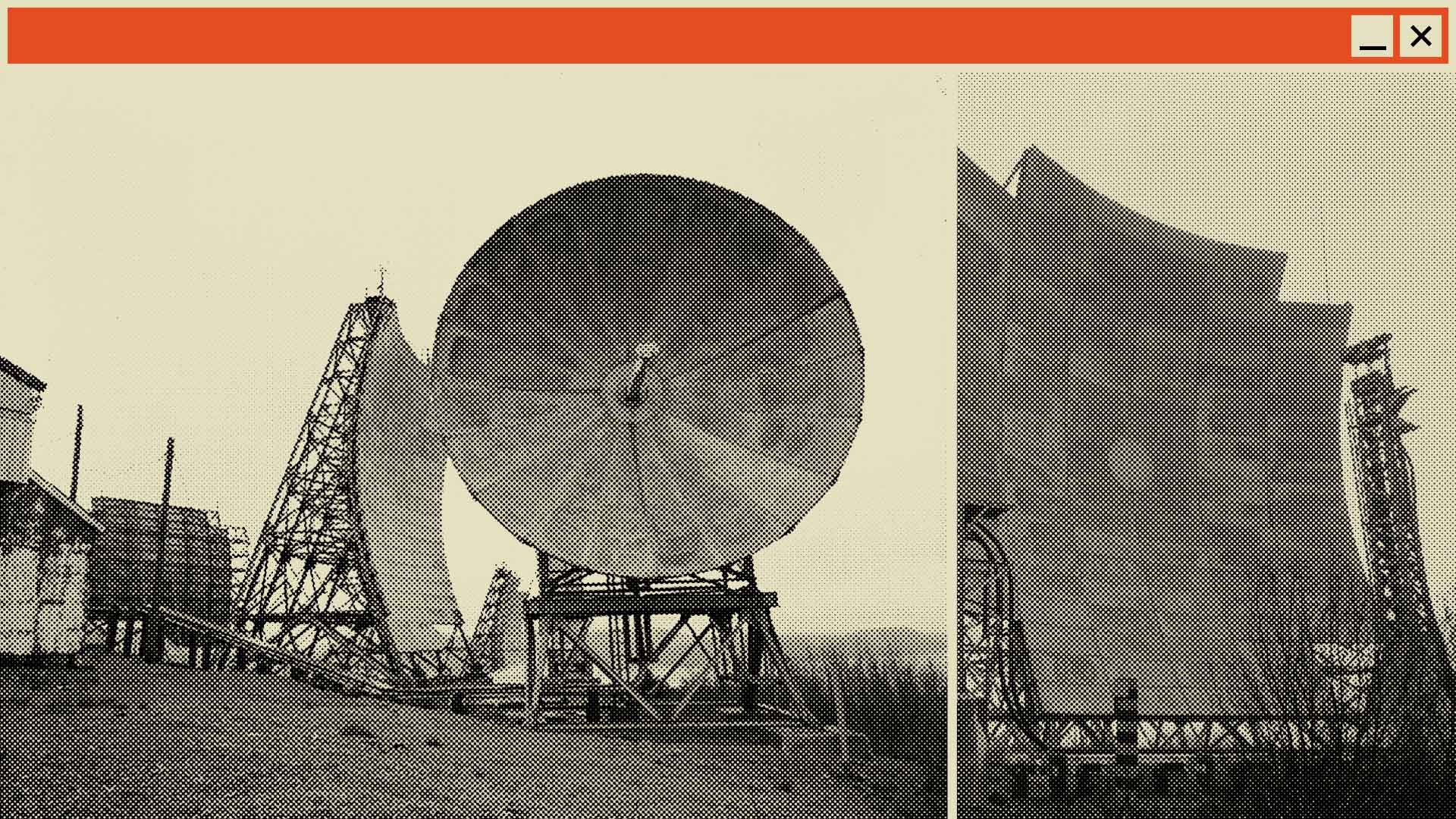

That wasn’t Harper’s only pre-espionage intersection with nuclear defense. Harper had this incredible little chapter of his life—that we couldn’t fit into in the podcast—working on something called the “White Alice Project.” An initiative of the U.S. Air Force, White Alice was a massive early-warning communications network then being installed throughout remote locations in Alaska. In case Moscow launched a nuclear attack on the U.S., White Alice sites would give America more time to mount a response.

At first, Harper worked on the project from the Bay Area, but in 1957, he moved to Alaska to do on-the-ground work there. For 18 months, he toiled above the Arctic Circle. Initially, he was stationed at a larger outpost in northern Alaska. Harper told me he fell in love with a Native Alaskan woman and was planning on marrying her and settling down there, but that his bosses actually flew up to the village to discourage his amorous impulses. (Who knows how differently Harper’s life might have turned out if they hadn’t intervened?)

Instead, Harper’s bosses transferred him to a much smaller outpost, far from his potential bride-to-be. The base was called Tin City, and calling it “remote” doesn’t begin to do it justice. It is only 55 miles from Siberia—the closest point on the U.S. mainland to Russia. Sometimes, on a clear day, you actually can see Russia from there. In Tin City, Harper helped to build and maintain the Air Force’s early-warning communications equipment.

But, like many tech-savvy U.S. government employees and contractors today, Harper saw where the big money was in Silicon Valley: the start-up world, the private sector.

After Harper quit his “White Alice” job, he moved back to the valley and eventually began working at a firm called “Fairchild Semiconductor.” Now, if you’re a national security type, this name may not ring a bell. But if you’re a student of Silicon Valley, you know that the founding generation of “Fairchildren,” as they’re called, made the valley what it is today. One of these “Fairchildren” was Robert Noyce, who helped invent the silicon microchip, and founded Intel. Another was Gordon Moore, who also co-founded Intel. Eugene Kleiner, another Fairchild alumni, created Kleiner Perkins, a titan of the Silicon Valley venture capital scene. And so on.

James Harper arrived at Fairchild in the early 1970s, more than a decade after the founding generation did. But he was part of the same broad cultural milieu. And, like so many of his Silicon Valley contemporaries, Harper wanted to strike out on his own, and found his own firm.

And he did. While at Fairchild, in his spare time, Harper . . . invented the world’s first digital stopwatch. Harper soon founded Harper Time and Magnetics, which sold his signature “Accusplit” stopwatches.

If fate had been different, Harper’s invention might have made him a wildly wealthy man, a member of Silicon Valley’s moneyed aristocracy. But it didn’t. And so Harper became emblematic of another sort of Silicon Valley archetype: the scrappy founder who cuts corner, after corner, after corner. . .until this “fake it till you make it” ethos shades into rank criminality.

And that’s what Harper’s investors and business partners said occurred with “Harper Time and Magnetics”: Harper embezzled loads of funds form the company, and was kicked out of his own firm.

Like many of his contemporaries—and many Silicon Valley start-up folks today--Harper was a born risk-taker, a gambler.

(In fact, Harper was such a high-profile gambler that he told me he used to play Yahtzee regularly with Wilt Chamberlain—yes, that Wilt Chamberlain, one of the greatest NBA players of all time—at a San Francisco bar called the Pierce Street Annex when Chamberlain played for the Warriors in the early 1960s. I confirmed that such a bar did exist, but couldn’t corroborate his story of playing dice with the redoubtable Chamberlain.)

That sort of propensity for risk-taking, combined with a kind of devil-may-care hedonism, has fueled many Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. But it can also lead others down the primrose path.

And that’s precisely what happened with James Harper. Just after he was kicked out of own company for embezzlement, by the mid-1970s, he began secretly working for a ring of Silicon Valley-based technicians who were covertly supplying prohibited technology to the Soviet Bloc.

A few years after that, he was supplying Moscow’s allies with highly-sensitive, nuclear weapons-related secrets. Harper, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur, had made the ultimate pivot: to espionage. It’s one that others have also no doubt made since.

Listen to the latest episode of Spy Valley: An Engineer's Nuclear Betrayal

Silicon Valley blossoms, but there’s a dark side to all this newfound wealth and ambition. With his technical savvy and a penchant for scheming, one of America’s most notorious cold war nuclear spies gets his start.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.