How James Harper Became A One-Man Megasupplier Of Illegal Tech To Moscow

Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a parallel, mostly covert battle has been waged in the shadows.

Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a parallel, mostly covert battle has been waged in the shadows. This battle is aimed at choking off Russia's access to "dual use" technology that can help sustain its war effort.

It's an issue that sits at the intersection of espionage, trade, hi-tech, and military materiel.

"Dual use" refers to technology that can be used for civilian or military purposes. And in a world of ubiquitous microchips that power everything from refrigerators to dishwashers to coffee maker and toasters, the type of items that can be plausibly described as "dual use" are larger than ever. And, indeed, the U.S. has claimed that Moscow is using chips from household items to help repair its military equipment.

In response, the Biden administration has led a global crackdown on Russia's importation of a whole host of consumer goods. (It's not clear how successful this interdiction effort has been, thanks to friendly post-Soviet states serving as transshipment points for goods ultimately headed to Russia.)

Even long before Moscow's latest assault on Ukraine, certain types of goods were prohibited to export to Russia, like cutting-edge U.S.-made night-vision technology, as well as other U.S.-manufactured high-tech with military or intelligence applications.

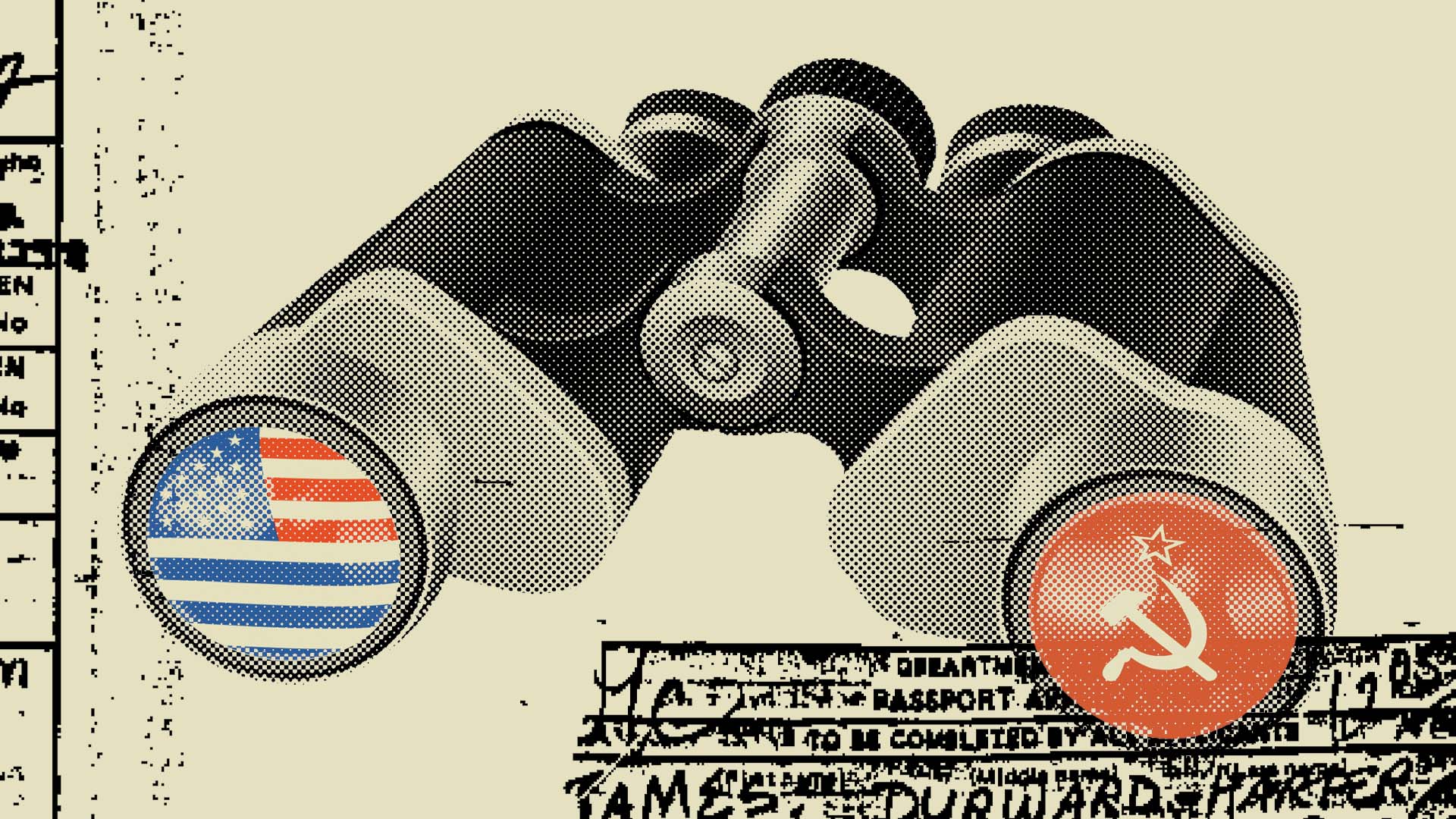

And, going back decades–indeed, at least to the 1970s, during the cold war–Moscow has sought to circumvent the U.S.'s technology-export restrictions by covertly purchasing coveted hi-tech. This illegal "tech transfer," as its called, can involve finished goods themselves–or the plans and trade secrets that might make domestic production of these goods in Russia itself possible.

Sometimes, Russian intelligence has set up commercial fronts to purchase and ship prohibited goods. Other times, its worked with unscrupulous traders and middlemen outside of Russia to get this export-controlled high-tech.

During the cold war, the KGB would also rely on the subordinate intelligence services from their Warsaw pact allies–like Poland, East Germany, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia–to help out.

And that's where Spy Valley's main character, James Harper, comes in. Starting in the mid-1970s, he was part of exactly this sort of illegal tech-transfer ring, helping other American agents get Communist Poland prohibited goods (for a fee, of course), which Warsaw would often dutifully pass on to Moscow.

By this period, the Soviet Bloc, desperate to keep pace with Western innovations in microelectronics, embarked on a massive espionage campaign to get their hands on prohibited tech however they could.

Harper’s work with the Poles–what became an espionage side hustle to his main gig stealing nuclear missile secrets–was part of this effort.

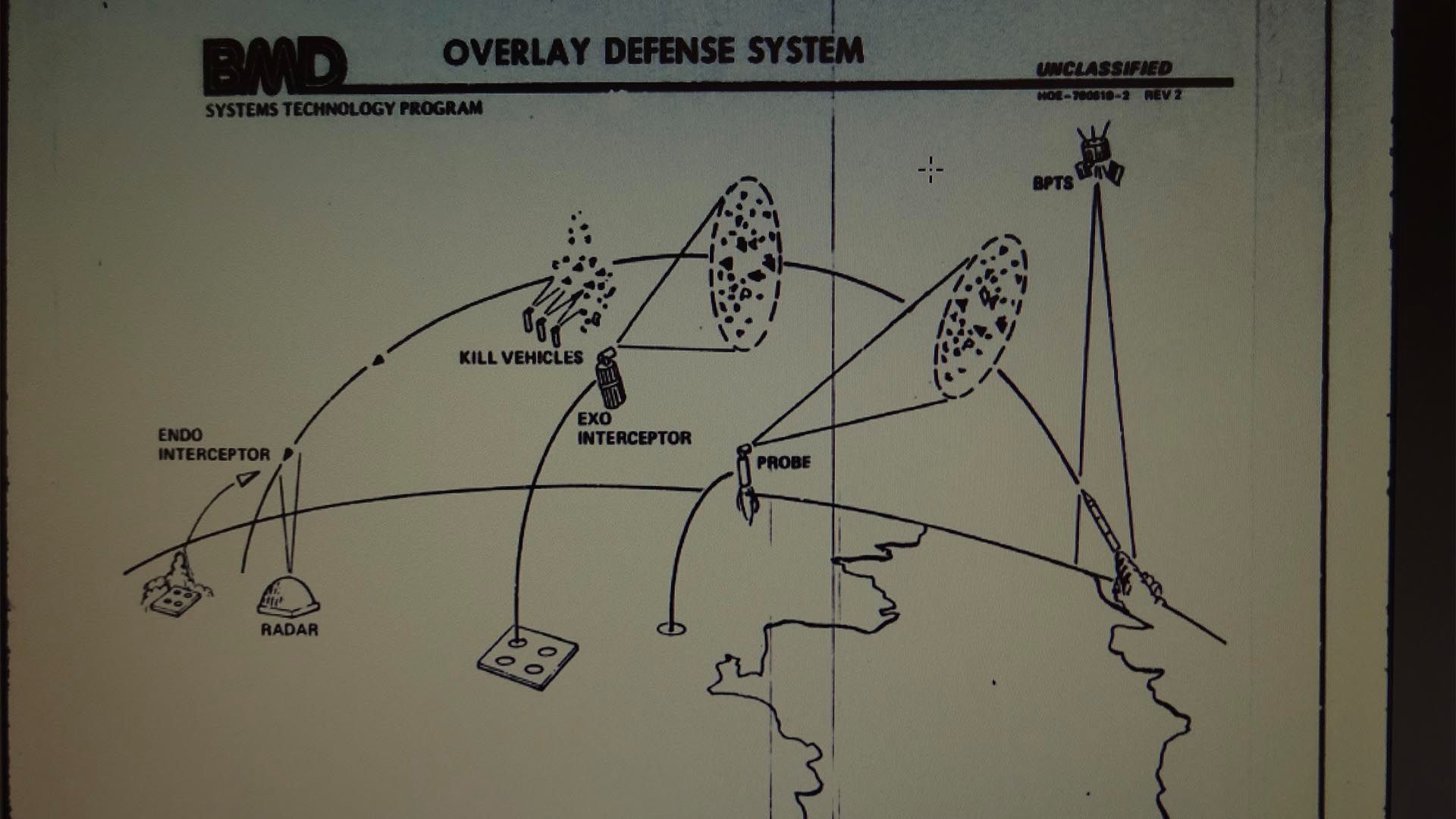

Now, this aspect of Harper’s spying–his sale of embargoed hi-tech, or other trade secrets–to the Poles may not seem as earth-shattering as the nuclear missile information.

But it was a big deal, too. Because Harper ended up serving, in essence, as a one-man megasupplier to the Eastern Bloc of prohibited tech.

Previously-published accounts of the Harper case tend to treat his illegal tech-transfer work for the Soviet Bloc as the entree to his espionage career–something that he dabbled in, and abandoned, after he starting selling nuclear missile-related documents to Moscow's allies.

But as I discovered, nothing could be further from the truth.

According to Harper's declassified Polish intelligence file, Harper continued to supply Warsaw with sensitive hi-tech information while he was selling them those missile documents. Harper even told me that, at certain points, the Poles seemed more interested in the hi-tech specs he was passing them than the missile docs.

Harper had a great hook-up, a girlfriend, who worked at a tech firm with access to semiconductor and other information coveted by communist-era Poles. But Harper had no idea just how valuable.

In fact, according to Harper’s Polish intelligence file, the Poles were basically fencing Harper’s stolen tech on behalf of the entire Soviet Bloc, taking order requests from Bulgarian and East German intelligence, and even the Soviet KGB itself.

And Harper’s tech made big waves. The East Germans, for instance, were over the moon about the microprocessor data Harper had pilfered on its behalf.

Here’s what Polish intelligence wrote about it:

For [our] German comrades, our assistance will accelerate implementing the production of these microprocessors by a minimum of 3 years. This has enormous significance to the economy of the GDR and socialist countries. . .

So Harper's stolen tech helped supercharge East German industry by 3 years, according to the Polish files.

For the Poles, this was a very lucrative scheme. The East Germans paid the Poles $150,000 (over half a million in today's dollars) for the tech stolen by Harper! That’s quite the tidy profit for a communist regime.

But that wasn't all. According to the intelligence files, the Poles turned around and sold some of this pilfered tech to Japan. Pretty entrepreneurial stuff. (Japan is a stalwart American ally, but–particularly in the 1980s–committed significant industrial espionage against the U.S.)

The Warsaw Pact is dead now, of course. And Moscow probably can't call on allies to help it procure prohibited technology quite like it did during the cold war. But there will always be a market in Russia–and China, and Iran–for men like James Harper, who have access to sensitive technology and are willing to cash in in the name of "free trade."

Listen to the latest episode of Spy Valley: An Engineer's Nuclear Betrayal

One million dollars, lives on the line, and a spy who keeps a diary. James Harper’s wild ride selling nuclear secrets as the cold war heats up—secrets that might still help Moscow in a nuclear exchange today.

Get in touch at zach@projectbrazen.com or securely at brushpass1@protonmail.com.