The Russian Spies of San Diego

It’s the early 1990s. The cold war has ended, and U.S. counterintelligence agents, though savoring their victory against the Soviets, are skeptical that the Russians were going to stop spying on the U.S. The old Eastern Bloc–Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and others–had turned decisively toward the West, but the situation in Russia was a lot hazier.

U.S. intelligence officials believed, correctly, that Moscow’s spy agencies were more likely to hedge their bets: the U.S. had been their “main enemy” for decades, and even the collapse of the Soviet Union wasn’t going to change that.

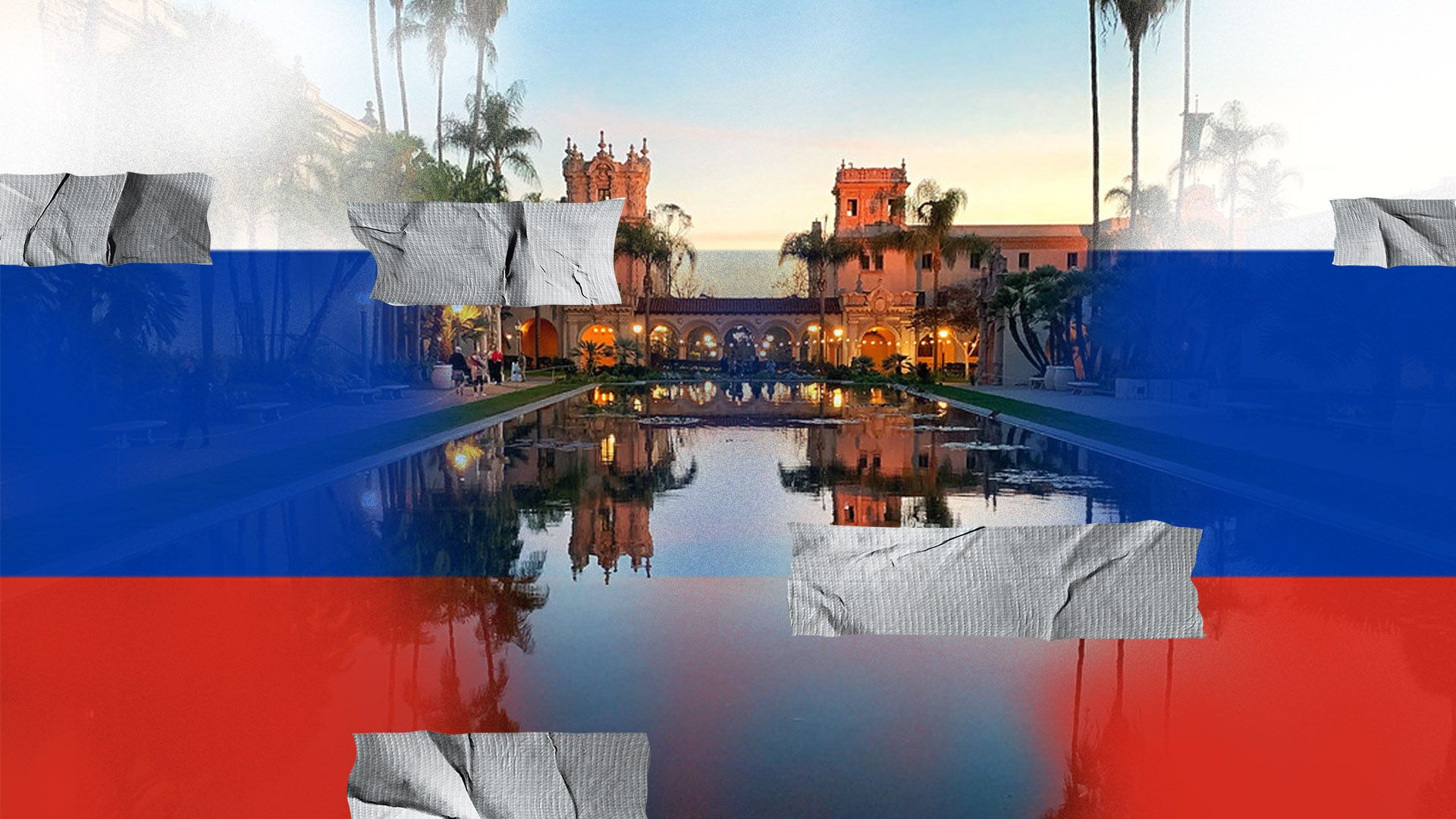

Around this time, Wayne Barnes, a veteran FBI spyhunter, was stationed in San Diego. Barnes was puzzling over a mystery. Recently, while driving through Balboa Park–a top tourist attraction in the city, most famous for being home to the San Diego Zoo–he had spotted small pieces of duct tape placed horizontally on the poles of street lights.

At first, Barnes thought the tape was a coincidence. Then he spotted another, and another–in all, upwards of twenty tape marks, all within the park.

Most people wouldn’t give these tiny pieces of tape a second glance. But in the world of espionage, this is a classic communications technique used by intelligence officers and their agents to signal that a package has been dropped, or picked up, somewhere known to the other party; they’re also used to request, or confirm, a clandestine meeting or handoff.

“I was astonished,” said Barnes. “It really sets the bee in the bonnet of U.S. intelligence when you see things like that.”

Was there a spy in San Diego?, Barnes wondered. The region was bursting with military targets, including a key naval base. For whom might he or she be working? The nearest Russian consulate was hundreds of miles north, in San Francisco. And the diplomats based there, who were subject to travel restrictions within the U.S., were surveilled closely by the FBI when they took approved trips down to southern California. China had a diplomatic outpost closer by, in Los Angeles, but at the time, Beijing’s spies weren’t generally known to use these kinds of signaling techniques.